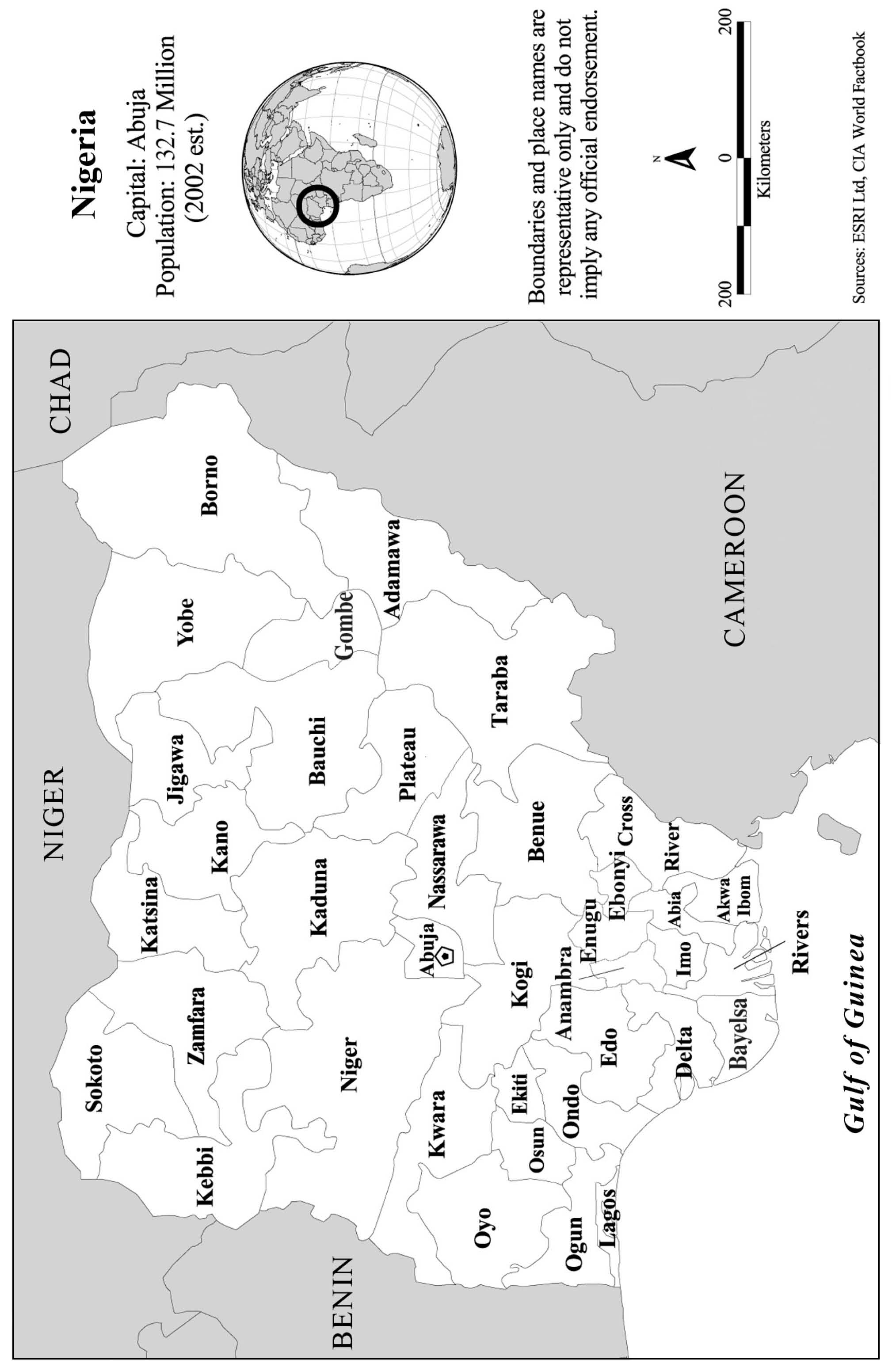

Nigeria has a population of about 130 million people.1 It consists of over 250 ethnic groups and over 100 languages. The official language is English; the major ethnic groups are the Hausa, Ibo, and Yoruba located in the north, east, and west of Nigeria, respectively. At Independence in 1960, these three groups held sway in these regions, hence, minority ethnic groups agitated for the creation of more states in order to break the yoke of the dominant three. The country’s fiscal federalism is predicated on economic, political, constitutional, local, and cultural developments. From three regions in 1960, the country grew to four regions in 1963. During the civil war of 1967–70, the country was carved into twelve states. By 1976, the states increased to nineteen, and by 1987 they increased to twenty-one. In August 1991, the number of states increased to thirty, and a separate Federal Capital Territory (fct), Abuja, was created in place of the old capital of Lagos. By October 1996, six additional states were created, bringing the total number to thirty-six. At present there are also 774 local governments. The country exports oil and the gnp per capita in 2003 stood at us$441. Nigeria operates a three-tier type of government (federal, state, and local).

The country runs a presidential system of government akin to that of the United States, with a bicameral legislature, a senate, and a house of representatives at the centre. In each state, there exists a house of assembly. The local governments have their councils. Members of all houses at the three tiers of government are elected during a general election. There are several political parties. However, two parties – the People’s Democratic Party and the All Nigeria Peoples’ Party – are dominant. The People’s Democratic Party is the party in power, and it controls twenty-seven states in the Federation. It has been in power since the return to democratic rule in 1999 and won re-election in 2003. The All Nigeria Peoples’ Party controls seven states, mainly in the north, while the Alliance for Democracy and the All Peoples Grand Alliance control one state each in the southwest (Lagos) and southeast (Anambra), respectively.

There are three branches of government: executive, legislative, and judiciary. The executive and legislative arms are elected along party lines. The Nigerian Constitution does not provide for independent candidature. The judiciary is made up of several tiers of courts, culminating in the Supreme Court. The Federal Appeals Court entertains appeals from the Federal High Courts and the State High Courts.

The fct, Abuja, also has its own High Court, as do the states in the Federation. The Customary and Sharia Courts, the Magistrate Courts in the states, and the fct run almost parallel to the system of High Courts. The judges and magistrates of the Customary and Magistrate Courts are learned in modern law, while those of the Sharia Courts, found mainly in the north, are learned in Islamic law.

Following years of military rule, the new presidential system faces a series of challenges. The introduction of Sharia law by some Muslim states in the north was the first problem for the new administration. There has been a rise in ethnic/sectional militant groups, such as the O’dua Peoples Congress in the southwest, the Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra (massop) in the southeast, and the numerous militant groups in the oil-producing Niger Delta Area.

The growth rate of Nigeria’s economy was about 3.5 percent in 2001–03. It relies heavily on crude petroleum, which provides about 90 percent of foreign exchange. The country was heavily indebted but recently obtained debt relief from the Paris Club. About two-thirds of the country’s debt has been “forgiven,” while the remaining one-third is to be paid in two installments.

The aim of this chapter is to examine the practice of fiscal federalism in Nigeria, paying attention to issues such as the structure of government, macroeconomic management, revenue-raising responsibilities, and challenges that will result in a better fiscal federalism for the country.2 The analysis confirms that, for Nigeria’s fiscal federalism to remain robust, the diverse ethnic groups must be willing to live together in a context of fairness and equity.

the st r u ctu re o f go vern me nt a n d di vi si on of fisc al po wer s

Nigeria operates a federal structure of government. The 1999 Constitution guarantees the existence of the federating units. The functions of the federal government are listed in the Exclusive List, while those of the states are in the concurrent list; where conflict exists, the exclusive functions of the federal government dominate.

The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria recognizes three tiers of government: federal, state, and local. The Constitution spells out the assignment of functions and areas of fiscal jurisdiction among the various units of the Nigerian federal system.

The current 1999 Constitution, in Section 4 (Second Schedule), indicates the Exclusive Legislative List, consisting of the responsibilities on which only the federal government can act, and the Concurrent Legislative List, on which both the federal and the state governments can act. In addition, Section 4 (7a) assigns the so-called residual functions to state governments. These are functions not specified either in the Exclusive List or the Concurrent Legislative List. Section 7 (5) (Fourth Schedule) of the Constitution provides for the establishment of local government councils with responsibilities set out in the Fourth Schedule of the Constitution.

Regarding the structure of government as defined in the Constitution, it is necessary to note the following:

f i sc al fed e ra lis m and ma c r oeco no mic man a gemen t

The major institutions driving economic policy include the Federal Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank of Nigeria. The Central Bank is responsible for monetary and exchange rate policy, while the Ministry of Finance oversees fiscal policy. In theory and practice, it is important that coordination exists. Hitherto in Nigeria there was no coordination between the Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank. In recent times, particularly from the year 2000, there seems to be coordination between the two.

Over the years, the problem with the economy has been persistent budget deficits. This economic phenomenon exists not only at the centre but also at the subnational government levels (state and local governments), where it also creates problems for the wider economy. Hence, there is the need for fiscal coordination at all levels.3

The Central Bank of Nigeria is independent with regard to the conduct of monetary policy and the maintenance of price stability. The law establishing the Central Bank guarantees that independence. However, the governor of the Central Bank informs the president about monetary, credit, and exchange rate issues. The independence of the Central Bank can be anchored on the recent example of bank consolidation, which required all banks to raise their capital to 25 billion naira. This policy has met no resistance from the presidency.

The Central Bank’s mandate goes beyond ensuring price stability: as part of the federal government’s economic team, it participates effectively in the overall management of the economy. The government’s present economic reform program, known as the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (needs), was conceptualized, formulated, and is now being implemented with the full participation of the Central Bank.4

The Central Bank has been struggling to reduce the inflation rate to the single-digit level in order to ensure a positive real interest rate. In addition, the bank is concerned with reducing the cost of funds in order to stimulate investment. The economy operates a managed float exchange rate regime. These issues form part of a broad macroeconomic framework for managing the Nigerian economy.

It was mentioned earlier that, if the assignment of functions in a federal system is discussed from the point of view of the major functions of government, the federal/national government would be in a better position to perform its stabilization function. Yet the federal system has inherent destabilizing characteristics due to the existence and fiscal perversity of sub-national governments. For instance, periods of excess oil revenue, when the economy is likely to be overheated, call for spending restraint. However, with increased revenue, the state and local governments usually increase their spending. During downturns, when efforts should be geared towards increasing spending, state and local governments are often forced to cut back on their spending, thereby compounding the problem of macroeconomic management at the national level.

Fiscal Responsibility Act

To improve the management of the economy at all levels of government, the federal government has proposed the Fiscal Responsibility Act. It aims at committing all tiers of government to effective, disciplined, and coordinated budgetary planning, implementation, and reporting. One of the major features of the act is that it institutionalizes a stabilization strategy to save windfall oil revenues in order to smooth consumption during periods of decline in oil revenues. Other features are purposeful investment of the windfall; reduction in fiscal deficits through the provision of guidelines against over-borrowing and incurring unjustified debts; standard formats for reporting and evaluating budgetary goals and performance; guidelines to stem the culture of indiscipline, waste, and corruption in public finance in order to improve transparency and accountability; and establishment of high standards of financial disclosure and public access to information on government finances. The Fiscal Responsibility Bill has gone through the various stages in the houses of Parliament and will soon become law.

Stabilization Fund

The concept of the Stabilization Fund, also referred to as the National Reserve Fund, or the Excess Crude Account, was introduced at the national level to moderate the impact of up and down swings in oil revenue on aggregate spending in the economy. It aims at creating a special holding account, whereby surpluses in oil revenue during periods of rising oil prices would be set aside and utilized during periods of fall in oil revenue in order to keep government spending stable. There is no doubt that the stabilization concept would be a useful tool in macroeconomic management. However, from past experiences, the problem was not with the idea of a reserve fund but, rather, with how it was managed and eventually utilized. The states had complained of their non-involvement in decisions on how the fund was to be utilized. Indeed, the federal government, especially during the military era, unilaterally utilized the fund however it pleased. Apparently, the federal government tended to confuse the Stabilization Fund with the establishment of the Contingencies Fund provided for in Section 83 of the Constitution. While the Contingencies Fund is also meant for urgent and unforeseen expenditures, its major characteristic is that it is to be established out of the federal government’s own money, unlike the Stabilization Fund, which is established with monies belonging to all the governments of the Federation. In 2001, the Contingencies Fund stood at N4.8 billion. It increased to N5.3 billion in 2002.5

It is also important to point out that the Supreme Court did not rule in April 2002 against the concept of the Stabilization Fund but, rather, against how it was funded (i.e., deducting it as a first charge on the Federation Account before the account is shared among the owners, the three tiers of government).6 In addition, it is important to establish proper ownership of the Stabilization Fund, whereby the contributions to it would be proportional to the relative shares of the different tiers of government in the Federation Account. This would ensure that each tier of government is fully aware of its share in the Stabilization Fund when it comes to disbursement. It would also reduce the temptation on the part of the federal government to see the fund as an additional source of revenue for its own use.

For now, the federal government controls the Stabilization Fund. In 2001, the Stabilization Fund stood at N6.4 billion; it increased to N7.5 billion in 2002 and to N10.4 billion in 2005. In 2005, state governments received a total of N1.5 billion from the stabilization fund.7

Borrowing and Taxation

Items 7 and 59 of the Exclusive Legislative List of the Constitution confer on the federal government exclusive rights over borrowing monies within and outside Nigeria for the purposes of the Federation or the state, and major taxes, including taxation of income, profits, and capital gains, respectively. But it does not appear that the federal government has ever had a firm grip on controlling borrowing by the various governments, including itself, especially in terms of the timing, purpose, and monitoring of the use of loans. It is hoped that, with the better management of available resources envisaged by the Fiscal Responsibility Act, there will be a reduction in deficit financing and, consequently, a reduction in public debt, at both national and subnational levels. At present, subnational governments can only obtain external loans with the approval of the federal government.

However, taxation has not proved to be a useful tool in managing aggregate spending in the economy. Outside corporate income tax, income tax has been of limited use in controlling spending in an economy dominated by oil revenues.

issues in revenue-raising responsibilities

This section discusses the assignment of expenditure responsibilities and the assignment of revenue powers.

Assignment of Expenditure Responsibilities

If political authority is divided among the different levels of government, then there is a need to determine the appropriate functions to be performed by each level. Ideally, two factors may influence the allocation of functions among the different levels of government. These are the geographic range of spillover effects, or benefits from collective action, and economies of scale. With respect to the geographic range of benefits, each function should be assigned to that level of government that coincides in size with the group that benefits from that activity. This implies that the na-tional/central (federal) government would provide those services that benefit the whole national population, while state and local governments would provide those services whose benefits are more divisible geographically. A federal arrangement enables the federating units to take advantage of economies of scale due to the fact that some functions could be performed more efficiently (in terms of lower unit cost) by the national government than by lower levels of government.8

The allocation of functions among federating units is more of a political than an economic exercise, and there may be no stated principles underlying such allocation in the Nigerian Federation. However, it is not unreasonable to infer that considerations of the extent of the benefit region (externalities) of government services and economies of scale must weigh heavily in the decision to allocate some functions to the federal government and others to state and local governments. Hence, those functions whose benefit region covers the entire country and/or that can be more efficiently performed at a national level have been assigned to the federal government. These include national defence, external relationships, banking, currency, coinage and legal tender, and weights and measures.

Functions whose benefit areas are more local than national but with the possibility of spillover effects – such as antiquities and archives; electric power; industrial, commercial, or agricultural development; scientific and technological research; and university, technological, and postprimary education – are on the Concurrent List. Finally, functions that are purely local in character in the sense that the benefits accrue, in the main, to limited geographic areas within the country, are usually assigned to local authorities. Such functions include the establishment and maintenance of cemeteries, markets, motor parks, public conveniences, refuse disposal, and construction and maintenance of local roads and streets. Table 3 contains a summary of the assignment of expenditure responsibilities in Nigeria.

It is also conventional to discuss the assignment of functions in a federal system from the point of view of the major functions of government – namely, allocation, distribution, and stabilization. At the theoretical level, it has been argued that the central government would be in a better position to perform the distribution and stabilization functions. Discussion of the allocation function is not all that simple because it depends on a number of factors, one of which is the division of functions between the private and the public sectors of the economy. The other types of publicly produced goods that are involved – private goods, impure public goods, and pure public goods – depend on the degree of market failure in their provision. For instance, it is questionable whether public production of a private good such as electricity and its placement under the federal government can still be justified on the basis of the failure of the market system to provide for such goods. In other words, not all publicly produced goods are public goods, and even in the case of pure public goods, as noted earlier, there is a distinction between national public goods whose spatial incidence covers the entire nation and local public goods whose spatial incidence is limited to particular geographic areas.

Table 1 Basic political and geographic indicators

Official name: Nigeria Population: 129.9 million Area (square kilometres): 923,768.64 square kilometres gdp per capita in us: $493.2 (2004) Constitution: 1999 (presidential) Constitutional status of local government: By election (third tier of government) Official language English Number and types of constituent units: federal, state, local governments, municipal governments Population, area, and per capita gdp in us$ of the largest constituent unit – not available. Population, area, and per capita gdp in us$ of the smallest constituent unit – not available. Currency: Naira = 100 kobo Federal capital: Abuja

Assignment of Revenue (Tax) Powers

A proper understanding of the basis of the allocation of tax powers requires a brief review of the evolution of the division of tax powers in the Nigerian federal system. Between 1914 and 1946, Nigeria operated a unitary system of government. With the creation of regional authorities in 1946, there was a need for some formalization of the fiscal relationship between central and regional authorities. Hence, the 1947 Constitution identified two sources of revenue for the regional authorities. One was “declared revenue derivable from within the region and the other was non-declared revenue, consisting of block grants from central revenue.”9 Within this framework, therefore, some of the issues that had to be resolved were the division of tax powers between central and regional authorities and the criteria for declaring any revenue source as regional.

The first Fiscal Commission, the Phillipson Commission, appointed in 1946, set out very stringent conditions for declaring any revenue source regional. For instance, “regional revenue sources would have to be essentially local in character for easy assessment and collection; regionally identifiable; and have no implications for national policy.”10 With these stringent conditions, it became obvious that very few revenue heads (taxes) would qualify as regional (now states and even local governments). The obvious implications would be that the revenue sources that would qualify as regional or subnational would be inadequate for the performance of subregional functions.

Thus, although both the Phillipson Commission and most of the subsequent commissions saw the merit of the principle of maximum independent revenue for the regions (now states) and, subsequently, local governments, they all ended on a pessimistic note about the scope for the enlargement of the tax jurisdiction of lower-level governments.11

We discuss briefly tax powers in Nigeria. Because of the limited scope for manoeuvreability already noted, there has been very little change in the allocation of tax powers over the years. The only notable exception was the reverse transfer of the legal aspects of the capital gains tax, personal income tax, and sales tax (now value-added tax) from state governments to the government of the Federation. It became obvious that these taxes do not fully satisfy the conditions required for them to be declared truly state taxes. The major sources of revenue – import duties, mining rents and royalties, petroleum profit tax, corporate income tax, excise duties and value-added tax, and personal income tax (legal basis only) – come under the jurisdiction of the federal government. The administration and collection is conducted by the states, which also retain the proceeds for their own use. One consequence of the concentration of revenue-taxing powers in the federal government is the dependence of lower-level governments on federal sources of funding but not on the federal government. The other is the imbalance between the functions constitutionally assigned to state and local governments and the tax powers available to them.

fiscal equality and efficiency concerns

and intergovernmental fiscal transfers

There is no doubt that fiscal arrangements are a consequence of a federal structure. However, the kinds of fiscal arrangements in place ought to affect the nature of the federal structure. The fundamental problem becomes how to devise a federal structure that would be conducive to national and equitable allocation of the country’s resources among the different tiers of government so as to reduce intergovernmental and intergroup tensions. Other problems in the country’s fiscal arrangement include power sharing and the consequent imbalance between the expenditure responsibilities assigned to the different levels of government and the tax powers available to them, state and local government dependence on federal sources of funding, and the concentration of spending powers on the part of the federal government.

Consequently, the government faces the challenges of vertical and horizontal fiscal gaps and how to overcome them. There is no systematic pattern of providing grants to lower levels of government. Where grants are provided, they follow an ad hoc pattern. The federal government makes vertical and horizontal allocations to lower levels based on a formula, which remains a subject of contention. Budget deficits are prevalent in the country’s federal system. The Nigerian Constitution established a Revenue Mobilization Allocation and Fiscal Commission (Section 153) with powers to review and recommend revenue-sharing rules in the Federation (Section 162).

Table 2 Nigeria: Legislative responsibility and actual provision of services by different orders of government

| Legislative responsibility (de jure) | Public service | Actual allocation of function (de facto) |

|---|---|---|

| Federal | Education (tertiary and secondary) | Federal and state |

| Federal/state | Education (primary) | Local |

| Federal/state/local | Health | Federal, state, and local |

| Federal | Defence | Federal |

| Federal/state | Law and order | Federal |

| Federal and state | Fire services | State |

The following section considers issues of power sharing and imbalance between assigned responsibilities and tax powers, revenue allocation, and the method used to channel allocations to local governments.

Power Sharing and Imbalance between Assigned Responsibilities and Tax Powers

In a federal structure, it is normal for each order of government to be given adequate resources to enable it to discharge its responsibilities. In practice, this does not run all that smoothly. Often, one order of government may end up with more financial power than it actually needs, while another may have less than it needs.

The fiscal arrangement in Nigeria is characterized by excessive concentration of fiscal powers in the federal government. Invariably, there is a lack of correspondence between the spending responsibilities and the tax powers and revenue resources assigned to different levels of government. The federal government is the “surplus unit” and the state and local governments are the “deficit units.”12 The allocation of tax powers centre on administrative efficiency and fiscal independence. The efficiency criterion insists that a tax be assigned to that order of government that will administer it efficiently (at minimum cost), while fiscal independence requires that each order of government raise adequate resources from the revenue sources assigned to it in order to meet its needs and responsibilities. Concerning tax powers, the efficiency criterion often conflicts with the principle of fiscal dependence. In Nigeria, weighting has always been in favour of the efficiency criterion, which allows for the concentration of taxing powers in the hands of the federal government.

The effect of concentrating tax powers in the federal government is the dependence of state and local governments on federal sources of funding, which is often confused with dependence on the centre. The federal government is assigned to administer the most lucrative sources of revenue because it is perceived to be in a better position to administer those taxes efficiently. Thus, the federal government administers those taxes on behalf of all the governments of the Federation. Hence, the federal government has no more right over the monies it collects than do the state and local governments. It follows that, in sharing the revenues collected by the federal government on behalf of itself and the other tiers of government, it is not correct to assert that the lower levels of government depend on the centre. In fact, the federal government is not constitutionally assigned to collect such revenues.13

Revenue Allocation

With respect to the reassignment of functions, since the federal government is the “surplus” unit, this would entail shifting functions from state and local governments to the federal government. However, given the principles that guide the allocation function, such reassignment of functions might necessitate assigning the functions that would otherwise be more suitable for lower-level governments. Nevertheless, there were some attempts in the past to shift some functions from the state governments to the federal government. For instance, as a result of its access to more elastic sources of revenue in the 1970s, the federal military government shifted such functions as university education and primary education and, to some extent, television and radio broadcasting and major newspapers from state and local governments to itself. On shifting tax powers from the surplus unit to the deficit units, given the principles that guide the allocation of tax powers in the Nigerian system, any realignment of tax powers to lower-level governments to match their expenditure responsibilities might entail transferring to state and local governments tax sources that they lack the capacity to administer.

In the Nigerian context, therefore, it would appear that the most viable option for remedying the problem of imbalance between the functions and the tax powers assigned to the different tiers of government is to make adjustments in the revenue-sharing formula. This issue is explored further below in the discussion of public revenues and unresolved issues that revolve around revenue allocation in Nigeria.

The Federation Account

Section 162 (1) of the current Constitution stipulates that the Federation shall maintain a special account to be called “the Federation Account” into

which shall be paid all revenues collected by the federal government. Section 162 (2) of the Constitution makes provisions for sharing the Federation Account among the three tiers of government, as already noted.

Before the Resource Control Suit,14 the areas of contention with respect to the Federation Account had to do with non-payment of some revenues collected by the federal government into the account and some deductions from the account before sharing among the three tiers of government. The Supreme Court decision declared both actions of the federal government illegal. However, the controversy over the deductions from the Federation Account, the so-called Special Fund, still rages. Prior to the Supreme Court verdict, 7.5 percent of the Federation Account was set aside

| and distributed as follows: | |

|---|---|

| Federal Capital Territory | 1.0% |

| Stabilization | 0.5% |

| Derivation | 1.0% |

| Development of mineral-producing areas | 3.0% |

| General ecology | 2.0% |

The sum set aside as the Special Fund and its allocation to various heads has changed over time.15

The current debate on the Special Fund tends to confuse the need for funding some activities with who foots the bill. Taking the Federal Capital Territory (fct) as an example, no one can fault the case for its development. However, there is also the need to develop the thirty-six state capitals, especially those in the newer states. Some of the state capitals still have the characteristics of a rural setting and need to be developed. As a matter of fact, there is a compelling reason for dispersing the high population centres concentrated around Lagos and Abuja to other parts of the country. Therefore, the development of state capitals points to a way out. If one accepts the case for the development of state capitals, which must be funded by state governments, there is no reason why the federal government could not fund the development of the fct out of its resources, especially considering the proportion of the Federation Account that goes to the federal government.

It should be noted that, when the Supreme Court, in its landmark decision of April 2002, voided the distribution of the Federation Account to the Special Fund, the federal government, by presidential order, simply transferred the Special Fund to the federal government’s share, thereby increasing it from 48.5 percent to 56 percent. This modification to the Revenue Allocation Act was unsuccessfully challenged at the Supreme Court by the state governments in January 2003. The court ruled that the president had the constitutional powers to make such an alteration to an act.

Often the case of funding the fct from the Federation Account hinges on the often misinterpreted Section 299 of the Constitution. It states that “the provision of this constitution shall apply to the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, as if it were one of the States of Federation.” However, subsequent Section 299 (a) elaborates on “the constitution applying to fct as if it were one of the states of the Federation” to mean that, just as in the case of states, the legislative powers, executive powers, and judicial powers are invested in the House of Assembly, the governor of the state, and the courts of the state, respectively. These powers in the case of the fct are vested in the National Assembly, the president of the Federation, and the courts established for the fct, respectively. Moreover, the First Schedule of the Constitution, Part 1, lists the states of the Federation without any mention of Abuja.

A further concern is that ecological disaster could occur anywhere in the country. Each level of government should have contingency plans to ameliorate the effects of such disasters. This would imply that the federal government, whose territory is the whole country, should also make provisions for intervening when disasters occur in the country, especially in those cases where the lower-level government may not be able to cope with the situation. It is also expected that, when the resource control controversy is finally settled, more resources will be under the control of mineral-producing areas to enable them to handle the development problems of their areas.16

Vertical Revenue Allocation

A lingering problem of vertical revenue allocation in Nigeria is how to devise a rational and equitable allocation of the country’s resources among the different tiers of government that would minimize intergovernment and intergroup tension and promote national unity and development. The federal government has been allocated a large proportion of the Federation Account relative to the states and local governments. Of interest here is whether the federal government’s retention of the lion’s share of the Federation Account could be justified on the basis of the relative weight of the functions assigned to it. Alternatively, the federal share might reflect a legacy of past thinking, which, in the absence of a viable private sector, perceived a leading role for the federal government in the field of economic development.

Weight of Federal Government Functions

Claiming that the share of the federal government is based on the weight of functions assigned to it does not tell the whole story. Indeed, many of the Fiscal Commissions had justified the assignment of more than 50 percent of the Federation Account to the federal government on that basis.16 Yet, there is no indication of the basis for assigning both quantitative and qualitative weights to such functions. For instance, with today’s costs, the whole of the federal budget may not be enough to “adequately” fund the various arms of the armed forces (military, navy, and air force). Moreover, it is important to bear in mind that the allocation of functions in a federal set-up does not necessarily connote an ordering of such functions in terms of the preferences of the people for whom the services are provided. The relative development of the private sector and the current emphasis on private sector-led development strategy imply that the federal government should move to limit its role to the regulatory aspects of some functions and to engage less in actual production. For example, the post office and nitel may not be needed with the proliferation of private courier services and gsm operators.17 Moreover, the current policy of privatization should reduce the expenditure responsibilities of the federal government, which could reduce its funding of public monopolies. These developments may lead to taking another look at the weight of federal functions and, by implication, the federal govern-ment’s share in the Federation Account. One thing that is certain is that an appropriate balance is yet to be struck in the use of revenue allocation to correct the imbalance between functions and tax powers assigned to state and local governments.

Federal Presence in the States

Perhaps the concentration of fiscal powers in the federal government would have been less objectionable if that government were expending its resources equitably for the good of all the components of the Nigerian Federation. “Federal presence” refers to the spatial pattern of federal government spending. It has been argued that federal government spending in a particular state would probably influence the relative distribution of state income to a much greater extent than does the direct revenue share received by the state from the Federation Account. Thus, a state that gets little or nothing from the Federation Account but attracts a preponderance of federal spending may, in the final analysis, be at a great advantage.18

The disparity in the development of different parts of the country, occasioned by the inequity in the spatial distribution of federal spending in the states, can only heighten intergroup tension. Such preferential treatment of some states violates the principle of equality among lower tiers of government. The current cries of marginalization and the controversy over resource control are cases in point. It is not surprising that some state governments, groups, and individuals are calling for the minimization or elimination of surplus funds in the hands of the federal government. Thus, while there is a need for the centre to be strong enough to maintain the unity of the component units and to give the country a sense of national direction, the essential pluralism of Nigeria must be recognized and respected. A situation in which too much financial power is left in the hands of one order of government tends to encourage prodigality and gross mismanagement of scarce resources on the part of that government, and this does not make for a workable federalism.19

Horizontal Revenue Allocation

One reason for intergovernmental transfers is to correct vertical imbalances that arise because the national government retains the major tax bases, leaving insufficient fiscal resources to the lower-level governments to meet their expenditure needs. Another reason for intergovernmental transfers is to correct horizontal imbalances. These may arise due to the fact that some jurisdictions have higher tax bases than do others or have higher (or extraordinary) expenditure needs than do others. The objective of the fiscal transfers is to try to close the gap between the fiscal capacities and fiscal needs of the subunits. The horizontal revenue allocation in Nigeria is, therefore, a sort of unconditional block grant to states and local governments to correct the horizontal fiscal imbalances among them. To what extent do the formulas or principles used for horizontal revenue allocation address the problem of horizontal fiscal imbalances? More fundamentally, what is the extent of horizontal fiscal imbalances among the states and local governments? This question cannot be satisfactorily addressed without some knowledge of the fiscal capacities and fiscal needs of the different subnational units. Although it deserves serious attention, excursion into these areas is outside the scope of this study. Another matter in contention is the formula for horizontal revenue allocation in Nigeria.

The formulas and principles that have been applied for horizontal revenue allocation use population as a factor. This tends to complicate the problem of having an accurate population census in the country as various states and groups accuse one another of manipulating the census figures in order to reap some relative advantage in the use of population as a principle in revenue allocation. In spite of this controversy, the fact still remains that government is about people, development is about people, and, in the end, government is about the welfare of the people. Therefore, population ought to continue to play a dominant role in horizontal revenue allocation in Nigeria.

The case for internal revenue effort is another factor influencing horizontal revenue allocation. Internal revenue effort would encourage the states and local governments to look inward and try to maximize their internally generated revenue potentials. However, using internal revenue effort as a factor runs into serious problems when it comes to operationalizing the concept. The Okigbo Fiscal Commission of 1980 proposed that the ratio of internal revenue to total expenditure be used as a measure of internal revenue effort. The government rejected that proposal, and rightly, too, on the ground that such a measure would unjustly penalize states that raise loans for their approved capital projects; rather, the government substituted the ratio of internal revenue over recurrent expenditure as a proxy for internal revenue effort. Admittedly, this measure is likely to ginger up the lower-level governments to make serious efforts to either increase their internal revenue or to put a lid on their recurrent spending. However, the flaw in the index is that it fails to take into account the fact that internal revenue effort is a function of two factors – taxable capacity and tax effort (including tax rates and efficiency in tax administration). Hence, a state with high taxable capacity but with lower tax rates and inefficient tax administration may still have higher internal revenue or a higher ratio of internal revenue to recurrent expenditure relative to another state with lower taxable capacity but higher tax effort. There is, therefore, an urgent need to devise a better index of tax effort. And, until such an index is devised, the weight currently given to internal revenue effort in horizontal revenue allocation should be very minimal.20

Land mass terrain was surreptitiously introduced into the history of revenue allocation in the 1980s, when the Shagari Administration used it to break the alliance between the Unity Party of Nigeria, the Great Nigerian Peoples Party, and the Peoples Redemption Party at the Joint Committee of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Joint Committee was appointed to reconcile the differences between the two bodies in their recommendations on revenue allocation. With the introduction of land mass at the Joint Committee meeting, states that stood to gain from its inclusion abandoned the alliance and voted with the ruling National Party of Nigeria. The recommendations of the Joint Committee were successfully challenged in court, in that they were presented to the president for assent without reference to the National Assembly, which set up the Joint Committee. Another reason had to do with the controversy that it was likely to generate. Land mass, as a principle of revenue allocation, was expunged from the recommendations of the Joint Committee that were sent to and approved by the National Assembly and subsequently signed into law. However, during the subsequent military regimes, landmass and terrain found their way back into the revenue allocation formula, without being thrown open to national debate (as is the case with most principles). Until that is done, the weight assigned to the principle of land mass and terrain should be greatly reduced.

Perhaps derivation as a principle of revenue allocation, or what has now come to be known as “resource control,”21 is the most controversial issue in revenue allocation in Nigeria. The derivation principle has been criticized as being capable of generating intergroup tension in a federation that strives for the unity of the component parts. This is because derivation tends to make the rich richer and the poor poorer. Not only was derivation the dominant principle of revenue allocation in the 1950s and 1960s but it was also vehemently defended by the power blocs that benefited from it. It was even defended on equity grounds – that the area from which the bulk of revenue is obtained should receive some share of the revenue beyond what other areas receive.22

Under military rule, and as the source and base of revenue changed, the principle of derivation became insignificant. The recently concluded National Political Reform Conference on resource control pointed to the fact that the appropriate weight to be given to the derivation principle in revenue allocation in Nigeria is yet to be determined.23

We strongly believe that emphasis on derivation encourages states and local governments to exploit their natural resource endowments. A situation in which groups clamour for recognition as states and local governments, without any regard for the sustainability of such units and mainly because they expect to be funded out of the Federation Account, does not make for true federalism.

Oil-Producing Areas and Resource Control

Crude oil production has been the most important economic activity in the Nigerian economy since the early 1970s. Its impact is not limited to the fact that it contributes almost 90 percent of Nigeria’s total foreign exchange earnings but also includes the fact that the national budget is predicated on the expected annual production and price of crude oil. Therefore, crude oil is the primary engine for national economic growth and development. It is, thus, quite reasonable to expect that the areas producing the nation’s crude oil would be very highly compensated for what is taken from them as well as for the devastation of the land engendered by the exploration process.

The Niger Delta region suffers from near total neglect by both the federal government, which claims ownership of the oil, and the multinational companies, which actually exploit the oil reserves. It is a picture of wanton environmental degradation of all types – land (despoliation of farmlands), water (destruction of fishing areas and sources of drinking water), and air (release of many pollutants causing diseases in humans, animals, and plants). The devastation and degradation suffered by the oil-producing areas are indications of the extraordinary expenditure needs of those areas that ought to be addressed by intergovernmental transfers. The federal government’s intervention through the Niger Delta Development Commission (nddc) is a welcome development. However, enough weight ought to be given to derivation to enable the state and local governments of the oil-producing areas to handle their developmental problems according to self-determined needs and priorities. The minimization of the derivation factor over the years – from the earlier 50 percent, to 1 percent, and now 13 percent – affects oil exploration and production, and it seems both unjust and unfair.

Channeling Allocations to Local Governments

Section 162 (5)–(6) of the 1999 Constitution says that the local government share of the Federation Account is to go to local government councils as follows:24

On payment into the State Joint Local Government Account from the government of the state, Section 162 (7) of the Constitution provides that each state shall pay to the local government councils in its area of jurisdiction such proportion of its total revenue on such terms and in such manner as may be prescribed by the National Assembly. A number of issues still remain unresolved with respect to channeling to local government councils amounts standing to their credit from the Federation Account and from the government of the state. The local government councils complain that not all the amounts due to them from the Federation Account are paid into the State Joint Local Government Account. They complain that state governments find all sorts of reasons to make deductions before the payment of Federation Account proceeds into the Joint Account and that, contrary to Section 162 (7) of the Constitution, hardly any state governments paid the stipulated percentage of their internally generated revenue into the Joint Account.

Another problem that arises with respect to the channeling of revenues to local governments relates to the apparent contradiction between Section 162 (5) and Section 162 (8) of the Constitution. Section 162 (5) states that payment to local government councils should be as prescribed by the National Assembly. Section 162 (8) states that “the amount standing to the credit of local government councils of a state shall be distributed among the local government councils of the state on such terms and in such manner as may be prescribed by the House of Assembly.” Thus, while the National Assembly prescribes the manner of payment of the proceeds of the Federation Account into the State Joint Local Government Account, the method of the distribution of amounts in the Joint Account to the local governments is to be determined by the House of Assembly of the state. A strict interpretation of these provisions is that the House of Assembly of the state is free to use, in the allocation of the Joint Account to the local governments, an entirely different set of principles from that used in allocating the Federation Account to local government councils. An obvious implication is that no local government council is in a position to legitimately compare what it receives from the Joint Account with what was due to it from the Federation Account. Even more frightful is the concern that some state governments may abuse this freedom and indulge in politically motivated discrimination in the allocation of the proceeds of the Joint Account among the local governments under their jurisdictions.

In an apparent attempt to resolve the problem of channeling resources to the local government councils, the National Assembly enacted the Monitoring of Revenue Allocation to Local Government Act, 2005. This act provides for the establishment of a body to be known as the State Joint Local Government Account Allocation Committee, whose purpose is to:

The monitoring process can detect divergence between total payments into the Joint Account and total payments to local government councils. However, it cannot legitimately detect divergence between allocations to individual local governments from the Federation Account and their receipts from the Joint Account. This is because different principles are used for payments from the Federation Account into the Joint Account and for the distribution of the Joint Account to the local governments. It is evident that intergovernmental fiscal arrangements in Nigeria have several challenges to overcome, particularly with regard to transfers from both the centre and state governments to local governments. In order to overcome some of these challenges, in 1989 the federal government established the Revenue Mobilization, Allocation, and Fiscal Commission.

Revenue Mobilization, Allocation, and Fiscal Commission

The Revenue Mobilization, Allocation, and Fiscal Commission is the federal government agency that determines the revenue-sharing formula, pending approval by both houses of Parliament. The commission was established in 1989 by Decree No. 49 and was inaugurated in 1990 in order to bring some sanity to the problem of revenue sharing in Nigeria. The commission was not effective during the military era because the government ignored its advice on revenue-sharing formulas. The situation changed in 1999, when the Constitution defined the membership of the commission as consisting of a chairperson and one member from each state of the Federation and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. The members were to be individuals who, in the opinion of the president, were persons of unquestionable integrity with requisite qualifications and experience.

The commission has the power:

The Commission does make recommendations on vertical and horizontal revenue allocations for the country. However, it is not uncommon for such recommendations to be adjusted by the federal government in its favour. Between January 1990 and June 1992, there were five revisions to the revenue allocation formula.

Table 3 Nigeria: Direct expenditures by function and level of government

| Function | Federal (%) | State or provinces (%) | Local (%) | All (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defence | 100 | – | – | 100 |

| Debt servicing | 100 | – | – | 100 |

| General administration | 70 | 20 | 10 | 100 |

| Law and order | 85 | 10 | 5 | 100 |

| Economic services | 80 | 15 | 5 | 100 |

| Social services | 70 | 20 | 10 | 100 |

| Health | 60 | 30 | 10 | 100 |

| Education | 60 | 20 | 20 | 100 |

| Subsidies | na | na | na | na |

| Total | 100 | |||

| Local public services | na | na | na | na |

Table 5 shows changes in vertical revenue allocations between 1992 and 2002. A notable change in the recent vertical revenue-sharing formula is the increase in the allocation to the local governments from the previous 15 percent to 20 percent to enable them to cope with funding primary education. In addition, as a result of the Supreme Court judgment on resource control, allocations to the Special Fund out of the Federation Account were declared illegal. However, in redistributing the Special Fund, the federal government appropriated 82.4 percent of the 7.5 percent of the fund, while only 17.6 percent was redistributed to the states (9.6 percent) and local governments (8.0 percent). This resulted in a phenomenal increase in the federal government’s share of the Federation Account, from 48.5 percent to 54.68 percent.

financing capital investment

The federal, state, and local governments finance capital projects through budgetary allocation; there is no law barring governments from raising invisible funds through the capital market. A few states, for example, Akwa Ibom, have floated bonds to finance selected projects. Federal government development stocks – long-term bonds – were introduced in 2003. This instrument deepens the financial market and encourages the government to source its long-term financing needs from the capital

Table 4 Nigeria: Tax assignment for various orders of government

Determination of shares in revenue (%)

Tax collection Federal State/ Local All Federal Base Rate and administration (%) province (%) (%) others (%)

Import duties Company income tax Withholding tax on companies Petroleum profit tax Capital gains tax Minus rents & royalties Stamp duties Value-added tax (vat) Education tax Personal income tax (except members of the armed forces, Nigerian police, residents in Abuja, staff of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and non-residents)

Federal Federal Federal 100 – –100 Federal Federal Federal/state 70 25 5100 Federal Federal Federal/state 100 – –100 Federal Federal Federal 100 – –100 Federal Federal Federal na na nana Federal Federal Federal 100 – –100 Federal Federal Federal/State na na – na Federal Federal Federal 100 – –100 Federal Federal Federal 100 – –100 Federal Federal Federal/State 80 20 100

State

Entertainment State State State na na nana Road taxes (motor vehicle and driver’s licences) State State State na na nana

Table 4 Nigeria: Tax assignment for various orders of government (Continued)

Determination of shares in revenue (%)

Tax collection Federal State/ Local All Federal Base Rate and administration (%) province (%) (%) others (%)

Pools, betting, and lotteries Gaming taxes Land registration Survey fees Development levies Property taxes

Local

Market and trading licences and fees Motor park dues Marriage, birth, and death Registration fees Bicycles, truck, canoe, and wheel barrow fees Public convenience, sewage, and refuse disposal fees Signboard and advertisement permit fees State State Federal State State/federal Local Local Local Local Local Local State State Federal State State Local Local Local Local Local Local State – ––– State – State – State – State/local

– ––

– ––

– ––

Local na Local na Local na

na nana na nana na nana

– Local – Local – Local –

– –– –– – –– ––

Table 5 Nigerian fiscal gaps

Total revenue collected Total expenditures Total revenue available

200120022003200420012002200320042001200220032004

National/federal 1427.5 1606.1 2011.6 2638.2 797.0 716.8 1023.2 1234.6 1018.0 1018.2 1226.0 1377.3 (billion naira)

States 573.5 670.0 855.0 1114.0 278.8 245.6 309.7 557.1 596.9 724.5 921.2 1125.0 (million naira)

Local 171.5 172.2 370.2 468.3 48.8 47.4 158.5 172.6 171.4 170.0 361.8 461.0 (million naira)

Source: Computed from Central Bank of Nigeria, Annual Report and Statement of Accounts, various issues.

market.25 The proposed fiscal act intends to provide guidelines limiting lower levels of government from foreign borrowing, except when they obtain approval from the federal government.

public management framework

The Federal Civil Service Commission is charged with the responsibility of hiring staff for the federal civil service. This commission cannot influence the hiring and firing of staff at lower levels of government. However, each tier of government has its own Civil Service Commission, and they are autonomous with regard to the hiring and firing of staff. It is very unusual for the federal government to undermine the authority of subnational governments in the area of employment matters.

Corruption is a serious matter in Nigeria. Transparency International lists Nigeria as one of the most corrupt countries in the world. Corruption produces distortions in the economy. Reasons postulated for corruption within the economy include low wages and salaries, greed, and a primitive accumulation instinct. Other forms of corruption include nepotism, tribalism, and favouritism. During the military era, there was no concerted effort to fight corruption. However, the present democratic experiment, which commenced in 1999, has demonstrated some seriousness in fighting corruption, despite the inherent constraints.

In fighting corruption the economy is seen as one. In other words, there are three tiers of government but one economy; therefore, the government agencies charged with fighting corruption cut across all tiers of government.26 Two prominent agencies are responsible for eradicating corruption: the Independent Corrupt Practice Commission (icpc) and the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (efcc). The efcc has spread its net over top government functionaries, such as state governors, members of Parliament (federal and state), and even the inspector-general of police. It is interesting to note that, recently, the former inspector-general of police was brought to court and jailed for embezzling public funds. The general opinion is that these anti-corruption agencies are moving in the right direction, and it is anticipated that their efforts can be sustained.

the way forward: contemporary issues in nigerian fiscal federalism

Given the dependence of all tiers of government on centrally collected revenue, especially the rent from oil and gas production, the most contentious and controversial issue in Nigerian fiscal federalism is the competing demands of each tier of government for a larger share of revenue.

Historically, the federal government, especially under successive military regimes, has retained the lion’s share of federally collected revenue. However, with the return of civil democratic rule in 1999, the states, especially in the resource-rich Niger Delta region, have been agitating for a greater share of national revenue.

The Nigerian Constitution makes provision for periodic review of the sharing rules to reflect changing economic and social realities. However, there has been no such review since the 1999 Constitution came into force. Therefore, agitation for a greater share of the so-called “national cake” has continued unabated.

The Constitution provides for derivation to be given a weight of not less than 13 percent in the sharing formula. Advocates of resource control in the Niger Delta region have continued to press for raising this floor to at least 25 percent.

There have also been controversies about the way the federal government operates the Federation Account. In its ruling in April 2002, the Supreme Court settled the issue of illegal and unconstitutional deductions from this account. However, the federal government continues to operate this account, disregarding the Constitution and the Supreme Court’s ruling. For example, the federal government continues to divert revenues meant for the Federation Account into so-called dedicated accounts such as the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (nnpc) expenditure account and the excess crude oil revenue account.

From these illegal accounts, the federal government proceeds to undertake unappropriated and unbudgeted expenditures. For example, recently the Revenue Mobilization Allocation and Fiscal Commission alerted the nation to the fact that the federal government had utilized the funds in the excess crude revenue account to pay Paris Club debts without authorization from the National Assembly. This happened in spite of the fact that these revenues belong jointly to all tiers of government in the Federation. In addition, some states and all local governments do not owe any Paris Club debt.

The federal government has similarly withdrawn money from these accounts to pay for the development of independent power plants, located solely in the southern part of the country, without appropriation from the National Assembly. The president himself admitted in a letter to the National Assembly that he withdrew funds from the excess crude revenue account to pay for the completion of the National Population Census. However, if constitutional federalism is to be protected and promoted and democracy itself is to be sustained in the country, this throwback from the decade of military dictatorship must be discontinued.

Flowing from all this is the contentious issue of who is the custodian of the Federation Account. The federal government has, to all intents and purposes, conducted itself not as just the custodian but also as the owner of the Federation Account. This claim was, however, not sustained in the judgment of the Supreme Court in the case of Lagos State versus the federal government.27 The court held that the federal government has not been conferred with the powers of custodian and trustee to this account and, therefore, cannot proceed to operate it in any manner as it deems fit. The Constitution does not confer on the president the right to withhold funds meant for any government in the Federation.

It was in order to avert the illegal operations and unconstitutional acts of the federal government with respect to the operation of the Federation Account that the National Political Reform Conference recommended the creation of the position of accountant general of the Federation. This position is separate from the accountant general of the federal government and is to be responsible for the maintenance and operation of the Federation Account.

The National Political Reform Conference

The recently concluded National Political Reform Conference further cements the notion that perhaps the Nigerian Federation is still fragile. It was widely reported that South-South delegates (i.e., those from the Niger Delta region) staged a walkout at the conference over the proposed marginal increment of the weight assigned to the derivation principle from 13 percent to 17 percent. The South-South delegates had demanded 50 percent. Despite the walkout, the conference concluded its deliberations and presented its report to the president, who, in turn, presented it to a joint session of the House of Representatives and the Senate. It is evident that the Conference could not agree on the issue of resource control. The heated debate on resource control and some unpleasant pronouncements on the matter by some delegates highlight the fundamental problems in Nigeria’s fiscal federalism.

Another burning matter concerns political power sharing among the different levels of government and the six geo-political zones. For federalism to work, the federating units must agree on some workable formula for sharing power. Power sharing should include which zone is going to account for the position of president. The same agitation is found both at the state and local government levels with regard to governors and council chairs, respectively.

The main purpose of the National Political Reform Conference was to discuss and find solutions to burning issues affecting Nigeria. While there were broad agreements on such areas as the economy, foreign policy, education, youth, and gender, the discordant voices on resource control and power sharing, among others, are reminders of the fragility of Nigeria’s federal system. It should also be noted that the conference had no constitutional or statutory mandate to implement its decisions. Perhaps this explains why the president submitted the report to both houses of Parliament. It is hoped that the National Assembly will deliberate on the report and implement those aspects of the recommendations that will benefit the country.

conclusion

There is no doubt that the practice of fiscal federalism in Nigeria has generated contentious issues, particularly around factors that would ensure an equitable and stable revenue allocation among the three levels of government. These factors include, among others:

If Nigeria is to remain a federation, then meaningful dialogue and compromises ought to guide deliberations aimed at reducing the tensions emanating from the practice of fiscal federalism. This would help to guarantee the sustained implementation of reforms.

notes

I wish to acknowledge the comments of the referees, particularly Chichi Ashwe and

John Kincaid. Their suggestions have improved this chapter; however, the usual

disclaimer applies. 1 This is an estimate. See the Nigerian government’s website:

gov.ng>. A national census was conducted in April–May 2006; the results are still

expected. 2 There are several studies of Nigeria’s fiscal federalism. For example, see Adedotun

O. Phillips, “Four Decades of Fiscal Federalism in Nigeria,” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 21 (1991): 103–11; John Kincaid and G. Allan Tarr, eds., Constitutional Origins, Structure, and Change in Federal Countries (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005), 240–75; and B.O. Nwabueze, Federalism in Nigeria under the Presidential Constitution (Lagos: State Ministry of Lagos, 2002), 4–55.

3 Izevbuwa Osayimwese and Sunday Iyare, “The Economics of Nigerian Federalism: Selected Issues in Economics Management,” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 21

(1990): 89–101. See also Akpan H. Ekpo, “Fiscal Federalism: Nigeria’s Post- Independence Experience, 1960–90,” World Development 22 (8): 1129–46. 4 Central Bank of Nigeria, Annual Report and Statement of Accounts (Abuja: Central

Bank of Nigeria, 2004). See

lenged the federal government’s introduction of the on-shore and off-shore oil dichotomy for the purposes of revenue allocation. They also urged, among other demands, that the federal government pay the 13 percent derivation. The Supreme Court ruling touched on several matters, including the Stabilization Fund. See Udeme Ekpo, The Niger Delta and Oil Politics (Lagos: International Energy Communications, 2004), 159–241.

7 Central Bank of Nigeria, Annual Report and Statement of Accounts, 156–61. 8 G.F. Mbanefoh, “Federalism and Common Property,” Guardian, 20 February 1993,

13.

9 A. Adedeji, Nigerian Federal Finance (London: Hutchinson Educational, 1969). 10 P.N.C. Okigbo, Nigerian Public Finance (London: Longmans, 1965). 11 Ibid. 12 G.F. Mbanefoh, “Nigerian Fiscal Federalism: Assignment of Functions and Tax Pow

ers,” seminar organized by rmafc, Enugu, 21–23 April 1992. See also Akpan H.

Ekpo, Fiscal Theory and Policy: Selected Essays (Lagos: Somaprint, 2005). 13 Ibid. 14 The “resource control” suit refers to the attempt by some states to control re

sources in their jurisdiction by using the courts; it also implies their having more than a fair share (through the sharing formula) of mineral resources by emphasizing participation in the exploitation of such resources. At present, the formula allows 13 percent for derivation. When the states took the federal government to court, the latter was not even adhering to the 13 percent provided for in the Constitution.

15 Akpan H. Ekpo and Enamidem Ubok-Udom, eds., Issues in Fiscal Federalism and

Revenue Allocation in Nigeria (Ibadan: Future Publishing, 2003). 16 Ibid. 17 nitel is the government-owned telecommunications company. gsm operators in

the country now include Vmobile, mtn, and Globacom. See G.F. Mbanefoh and Akpan H. Ekpo, Review of Constitutional Provisions and Fiscal Federalism in Nigeria, Abuja: World Bank, 2005.

18 Federal Republic of Nigeria, Report of the Presidential Commission on Revenue Allocation, vol. 1, Main Report (Apapa: Government Press, 1977).

19 Akpan H. Ekpo,. “Fiscal Federalism and Local Government Finances in Nigeria,” in Nigerian Economic Society, Fiscal Federalism and Nigeria’s Economic Development (Ibadan: Nigerian Economic Society, 1999).

20 See Mbanefoh and Ekpo, Review of Constitutional Provisions.

21 It was expected that an increase in the weight attached to derivation might reduce the tension surrounding the control of petroleum resources by the Niger Delta region.

22 Victor B. Attah, “Fiscal Federalism in Nigeria: A Re-Examination of My Views,” remarks made by the Akwa Ibom State Governor during the Roundtable on Global Dialogue on Federalism, Uyo, 29 September 2005.

23 Ibid.

24 Federal Republic of Nigeria, Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 (Lagos: Government Press, 1999).

25 See Central Bank of Nigeria, Monetary Policy Circular (Abuja: Central Bank of Nigeria, 2004), 1–58.

26 Federal Republic of Nigeria, The Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Act, 2000. See also

27 On 19 April 2004, the Lagos State Government sued the federal government, challenging the authority of the latter to withhold its statutory allocation to the new fifty-seven local government councils it created. In its ruling the Supreme Court reaffirmed that no one tier of government had more rights than did any other over the Federation Account and that, thus, the federal government could not stop payment to the Lagos state government’s existing (not new) councils.