shankaran n a mbiar

This chapter presents an overview of the manner in which federalism is practised in Malaysia. Malaysia adopted a centrally dominated federal system because it was believed that such a system accorded well with national planning. Malaysia has progressed tremendously since the framing of the federal system. The initial reasoning behind the original intentions of such a system may no longer be valid, principally because of the level of development that has been achieved. However, it appears that the dominant central role is retained because it affords the central government a great measure of control over the state governments. It can be argued that this enables the central government to pursue its national agenda without being distracted by the individual demands of the states. A second possible reason is that a centralized system allows the ruling party, through the central government, to ensure that a system of reward and punishment is preserved. This leads to state governments run by the ruling party or its component parties being favoured in terms of fiscal allocations, while those ruled by the opposition parties are disfavoured. Two issues are at stake here. First, political considerations are intertwined with development and fiscal issues. Second, the central government’s aspirations take precedence over the needs of the states.

The next section provides a broad overview of Malaysia’s geographical location as well as some of its main indicators. This is followed by a discussion of the structure of the government. Following a brief outline of the governmental system, I outline the division of fiscal powers, mentioning some of the areas of conflict that arise from this division. The third section addresses the issue of how fiscal policy is employed in the context of macroeconomic management, while the fourth section discusses how responsibilities for raising revenue are split between the central government and the states. The fifth section attends to the role of intergovernmental transfers within the context of equity and efficiency. This is followed by a section on the respective roles of the central and state governments with respect to capital investment. Subsequently, I discuss some issues relating to public management, after which I attempt to indicate the way ahead.

ov e r v i e w

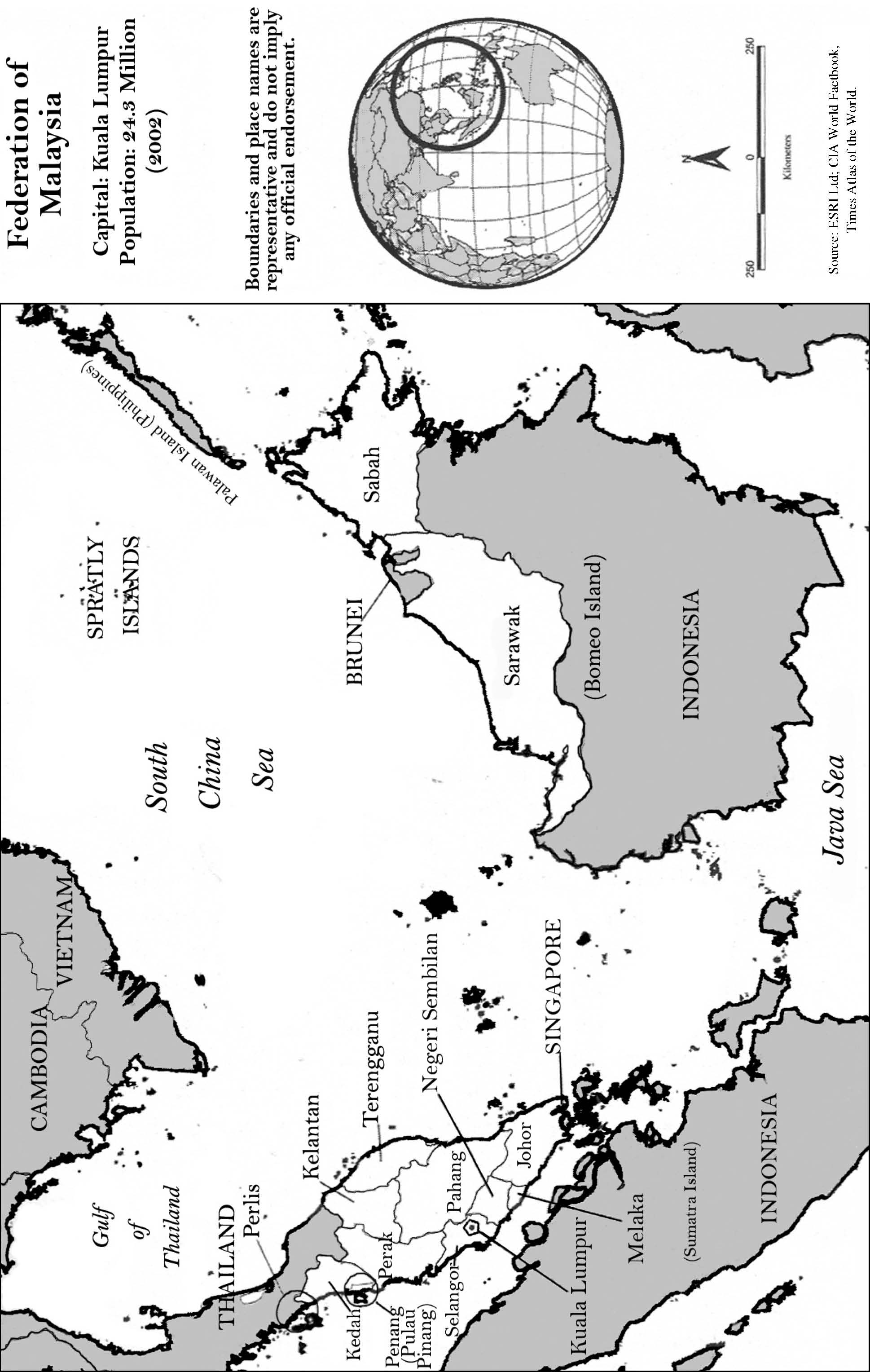

Malaysia is, in part, a peninsula that lies to the south of Thailand and is surrounded by the South China Sea to its east and the Straits of Malacca to its west. This part of Malaysia is referred to as Peninsular Malaysia, or West Malaysia. The states of Sabah and Sarawak constitute East Malaysia and are both a part of the island of Borneo. West Malaysia, which is at the tip of mainland Southeast Asia, is separated from East Malaysia by the South China Sea. West Malaysia consists of the states of Kelantan, Terengganu, Pahang, Johor, Melaka, Negeri Sembilan, Selangor, Perak, Kedah, Penang, and Perlis. Malaysia is a federal state comprised of thirteen states and three federal territories (i.e., Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya, and Labuan).

In all, Malaysia is made up of a landmass of 329,736 square kilometres, with East Malaysia accounting for 198,154 square kilometres. Sarawak, with 124,445 square kilometres, is the larger of the two states in East Malaysia; Sabah accounts for 73,709 square kilometres. Malaysia has a population of about 25 million people, with the vast majority (94 percent) being Malaysian citizens. Malaysia is a multi-ethnic country, the bulk of the population being Malays (65 percent). Chinese account for about 25 percent of the population, and Indians are a small minority at 7.7 percent. The rest of the population is made up of members of indigenous tribes and Eurasians as well as those of Cambodian, Thai, and Vietnamese ethnic descent. In Peninsular Malaysia, the Malays, Chinese, and Indians are the dominant ethnic groups, a situation that differs from that in East Malaysia, where non-Malay indigenous people form the majority of the population. Malays and Chinese jointly constitute a little less than half the population in East Malaysia.

Aside from this ethnic division, the Constitution defines a category known as the “Bumiputera.” The Bumiputera are defined to include all ethnic Malays as well as those who have at least one parent who is a Malay and who participates in the Malay culture. By definition, Malays are Muslims. This is because the legal system does not generally allow conversion out of Islam, which would be deemed an act of apostasy. The indigenous tribes are also considered to be Bumiputera. This category has important implications, as we shall discover later in our discussion. It must be stated at this point that the critical importance that is given to the Bumiputera in the country’s policy space is due to the racial riots that erupted in May 1969. In large part, these riots were supposed to have been triggered by the economic disadvantage experienced by the Bumiputera. They gave rise to the New Economic Policy, which was aimed at correcting ethnically linked income disparities and helping those who had been excluded from economic participation.1

Malaysia gained Independence from the British in 1957. Since that time, Malaysia has evolved tremendously, shifting from an economy that was largely agricultural to one that emphasizes industrial development. In 1970, the country’s gross domestic product (gdp) (in current prices) was rm11.83 billion (about us$3.2 billion), and it rose to rm487.38 billion (about us$132.3 billion) in 2005. Concomitant with the increase in gdp, the level of gdp per capita has also increased. gdp per capita was rm18,652 (us$5,084) in 2005 as against rm1,087 in 1970. Malaysia can now be characterized as a country that is dependent on export-oriented manufacturing rather than on agriculture.2 Agriculture, which used to contribute about 39 percent of gdp in 1961, accounted for only 8 percent (at constant prices) of gdp in 2005. Manufacturing, which had a share of 9percent of gdp in 1961, more than doubled its share to 19.6 percent in 1980 and stood close to 32 percent in 2005. The share of the services sector in gdp has been growing steadily over the years, rising from 42.5 percent in 1961 to almost 58 percent in 2005.

The growth rates that Malaysia has been experiencing since Independence are consonant with the shift in sector emphasis. Strong export-led growth is in large part responsible for the remarkable growth rates that the country has experienced.3 In the 1970s, the average growth rate was

The macroeconomic numbers are testimony to Malaysia’s sound trade and investment policies as well as to its prudent macroeconomic management, which have produced a resilient economy that is able to withstand external shocks. The government in Malaysia is optimistic about the coun-try’s achievements, especially its resolve to achieve developed country status by the year 2020. This vision was encapsulated as a policy statement by the previous prime minister, Mahathir Mohammad, and has been referred to as Malaysia’s Vision 2020.

the str u ctu re o f go vern me nt an d di vi si on of fisc al po wer s

In 1956, the Reid Commission was formed with the express purpose of making recommendations for a “federal constitution” for the Federation

of Malaya. This commission recommended a federal state. The Constitution of 1957 was a revision of the Reid Report Draft Constitution. As recommended by the Reid Commission, the Constitution of 1957 granted strong powers to the centre; the states were equal in their status vis-à-vis each other but not to the centre; and the center was envisaged as controlling all essential matters.4 There have been changes in the composition of the federation since Independence. In 1963, Sabah, Sarawak, and Singapore were included in the federation, necessitating an amendment to the Constitution. A subsequent amendment to the Constitution was necessary in 1966 to accommodate Singapore’s decision to leave the federation.

Malaysia is a constitutional monarchy that upholds parliamentary de-mocracy.5 The Parliament is bicameral, consisting of the House of Representatives (Dewan Rakyat) and the Senate (Dewan Negara). The Senate is a non-elected upper house, and the House of Representatives is an elected lower house. The Senate is composed of sixty-nine members. Each of the thirteen states appoints two senators, and the king, on the advice of the prime minister, appoints forty-three senators. Clearly, the representatives from the states are outnumbered by those who are federally appointed. The king, or Yang di Pertuan Agong, heads the Parliament and has a five-year term. He is appointed from the Conference of Rulers, which is established by the Constitution. The Conference of Rulers is made up of the hereditary rulers from nine states in Peninsula Malaysia and the governors (Yang di Pertuan Negeri) of Penang, Melaka, Sabah, and Sarawak, which do not have rulers. The governors do not play a part in the appointment of the king but are appointed by him every four years.

The Constitution of Malaysia divides the authority of the federation into its legislative, judicial, and executive authority.6 In consonance with the notion of federalism, the separation of power occurs in the federal and state spheres. Federal executive authority (or the power to govern), under Article 39 of the Constitution, lies in the office of the king, but can be exercised by the Cabinet headed by the prime minister. The prime minister and the Cabinet are responsible to the King. Judicial power, as stated in Article 121(1) of the Constitution, is vested in the Federal Court, the High Courts (the High Court of Malaysia and the High Court of Borneo), and the Subordinate Courts, which consist of the Sessions Courts, Magistrates’ Courts, and Penghulu’s (or village headman’s) Courts. The states do not have courts of their own; and they do not have their own constitutions.

The legislative authority, or the power to make laws, raise taxes, and authorize expenditures, is distributed between the federal and state governments. The Ninth Schedule of the Federal Constitution lists the division of legislative powers between the federal and state governments. Legislative power is vested in the federal Parliament. In the states, executive authority rests with the rulers (for the nine states) and governors (in the case of Penang, Melaka, Sabah, and Sarawak), who are the ceremonial heads. Each state has an executive council (exco), and this is the equivalent of the Cabinet in the state sphere. Elections for membership in the exco are held every five years. The exco is chaired by the Menteri Besar, or chief minister. The position of chief minister applies to the states of Penang, Melaka, Sabah, and Sarawak; all other states have Menteri Besars. Each state has its own legislature, or state legislative assembly, which is formed by members who are elected every five years.

The Ninth Schedule of the Constitution details the distribution of legislative powers and responsibilities between the federal and state governments. There are three lists that have been drawn out: a federal list, a state list, and a concurrent list. The federal list includes items such as external affairs, defence, internal security, civil and criminal law, and administrative justice. The following matters are also under the federal list: (1) trade, commerce, and industry; (2) shipping, navigation, and fisheries; (3) communication and transport; and (4) medicine and health. Those matters that have been categorized as being under the purview of the states include Muslim affairs and customs, native laws and customs, agriculture and forestry, local government, local public services, boarding houses, burial grounds, markets and fairs, and the licensing of theatres and cinemas. Finally, the concurrent list includes social welfare, scholarships, town and country planning, drainage and irrigation, housing, culture and sports, and public health.

The states, as provided for by the federal Constitution, have jurisdiction over local government. Local government can be divided into rural district councils and urban centres, with city councils and municipalities falling under the latter category.7 Regardless of the type of local government (i.e., rural or urban in character), all local governments perform the same functions. State governments, which are elected every five years, have the mandate to appoint the presidents who head the various councils (district, city, or municipal). Similarly, the councillors are also appointed positions. These appointments are for a period of three years, subject to reappointment if deemed suitable by the state governments. The councils operate through a committee structure, with the state governments establishing executive or other committees that are chaired by the council president.

State governments have to deal with three problems. First, they have to contend with the problem of credibility. Although the state legislature is elected, the members of the local councils are not elected representatives. Since 1965, local councils have not been elected. This was a consequence of the Emergency (Suspension of Local Government Elections) Regulations (1965) and the Emergency (Suspension of Local Government Elections) Amendment Regulations (1965). Being appointed, local councils do not have the credibility that goes with having passed through an electoral process. As far as the lower layers in the government hierarchy are concerned, they are fraught with the problem of credibility, something that weakens state governments.

Second, local council members are accountable to their respective political parties rather than to their constituencies. With the present arrangement, when there is a conflict of interest between the needs of the citizens in various constituencies and the overall goals of the federal government, it is more likely that the federal agenda will prevail. Taking note that the ruling party is a coalition of several ethnically based parties, with the dominant party being the United Malay National Organization (umno), this does not rule out the possibility that umno’s agenda will ultimately hold sway. Doing away with a system of elections for membership into the local councils means that umno’s members exist in a state of tension as to whether their loyalties should rest with party leaders or the members of the public.

Third, matters are more distressing when one considers the manner in which the federal, state, and concurrent lists are delineated. It is undeniable that items such as external affairs, defence, federal citizenship, criminal and civil law, and internal security should fall directly under the scope of the centre. However, an examination of the state list reveals that it is extremely restrictive. Aside from areas such as local government and public services, state government machinery, and state works and water, there is little that is within the ambit of the state to direct the nature or course of its own development. Native law, cadastral land surveys, and libraries and museums are among the other issues over which the state has control. Clearly, those areas that are under the state list are either those that only the state can handle (such as local government and state works) or those that are of little interest to the centre (such as land surveys, libraries, and museums). Substantial issues are either directly determined by the centre or are done concurrently.

It is disconcerting that the state has no control over crucial issues that have a bearing on its developmental progress. Important issues such as communication, transport, education, and health are entirely beyond the scope of the state. This restricts its ability to exercise its influence over these matters, leaving the economic development of states very much to the discretion of the centre. Penang, for instance, has long complained about its worsening traffic congestion and the need for a second bridge linking it with the mainland. Penang had to wait for the Ninth Malaysia Plan (9mp) to make federal allocations for the improvement of transportation within the island as well as for the provision of a second bridge to connect it to Peninsular Malaysia.

Refusing to allow the state governments to decide on education is another instance of the centre’s reluctance to distribute power and responsibilities to the states. There are reports that some schools in rural areas and on plantations are poorly equipped and maintained. One conjectures that, if state governments had been responsible for education, then assistance might have been more forthcoming. Besides, it would have been easier to pressure state governments on the performance of schools if they were a state affair. Rather than grant some autonomy over education to the states, the centre has been keen to use education as an instrument to garner votes in the general elections. As part of its campaign for the last two general elections, the ruling party, Barisan Nasional (bn), has promised to build a university for Kelantan, which is ruled by the opposition party, Parti Islam SeMalaysia (pas), or Pan Malaysian Islamic Party. This promise will be fulfilled because bn regained some control in Kelantan in the last general elections. While bn is composed of three dominant parties that represent the three major ethnic communities in Malaysia, pas is an Islamic party that has built its campaign on returning Malaysia to an Islamic state and institutionalizing Islamic law. The plan to allocate funds to Kelantan for the establishment of a university has been announced in the 9mp. This clearly indicates that development considerations are sometimes relegated to secondary status, with political leverage being accorded primacy.

The central government seems to be unwilling to decentralize its powers to the states. This may be because of the historical origins of Malaysia’s Constitution. As mentioned earlier, the Reid Commission Report was the forerunner to the Constitution. The Reid Commission argued for a federal state with a strong central bias. While the power of the states in areas like land could be tolerated, it was felt that the centre should be in a position to avoid any actions from the states that might interfere with the national planning process. In regard to financial relations, the Reid Commission thought that financial autonomy could be achieved by reducing the range of responsibilities that should be accorded to the states and ensuring that they would be provided with compulsory grants from the centre. This, perhaps, has led to the concentration of power enjoyed by the central government. It is easy to see why the historical roots for the strong central bias are still being maintained.

The present system is, arguably, a system that allows the bn to maintain its hold over the state governments. Under this system, it is possible to punish those states that are led by opposition parties, while rewarding those that are led by the bn.8 The tight control that is exercised by the central government ensures that the state governments must rely on the centre for the implementation of development projects. It also encourages the central government to check the growth of opposition parties, as was seen in the case of the promised allocations for building a university in Kelantan. If, for example, the central government were to support the founding of a university in a pas-dominated state, this would amount to signalling that pas, a theocratic party, could succeed in achieving the needs of its constituency. This would spark greater interest in pas as a viable political alternative, something that threatens umno, which claims to support the rights of the Bumiputera.

The fiscal issues relating to petroleum production also illustrate the bias that can be exercised by the central government.9 The 1974 Petroleum Development Act stipulates that 5 percent of the royalty on the gross value of petroleum output should go to the government of the oil-producing state, 5 percent to the federal government, 20 percent to cost recovery, and 21 percent (for profits) to the producer company. The remaining 49 percent should go to Petroliam Nasional Berhad (Petronas), a company established by Parliament through the Petroleum Development Act (Article 144). However, there are only three petroleum-producing states: Terengganu, Sabah, and Sarawak.

The fiscal issues relating to petroleum production give rise to several points of contention. Through the Petroleum Development Act, all states are bound by law to give Petronas sole rights for oil and gas exploration in their respective territories. This implies that state governments have no mandate to initiate or develop the oil industry in their own states; and they do not have any right to participate in the gains accrued from profits obtained in this industry, beyond the 5 percent that is due to them as stipulated by the act. The act states that only Petronas is vested with the power to explore for oil and gas and to develop all aspects of the industry relating to petroleum and its products, including all downstream activities. Further, Petronas is only answerable to the prime minister (not to the state governments). The relative exclusion of the oil-producing states from the fiscal benefits accruing from oil in their own states is compounded by the fact that they have no jurisdiction whatsoever over Petronas. The fiscal monopoly that the centre wields over the oil-producing states abundantly illustrates that the federal government is interested in increasing the concentration of powers and responsibilities of the centre.

The three oil-producing states – Terengganu, Sabah, and Sarawak – do not emerge among the richer states in Malaysia. In fact, on the basis of a number of economic indicators, these three states do not fare well. In terms of the incidence of poverty, two of the three states perform poorly. Sabah has the highest incidence of poverty in Malaysia, while Terengganu is the third poorest state in the country. In terms of the development composite index, all three states are classified as less developed states. States like Penang, Selangor, and Kuala Lumpur (a federal territory) obtain a score of about 139 on average, whereas Sabah, Sarawak, and Terengganu obtain an average of 120 on the development composite index. In spite of these disparities, the federal government has not been inclined to allocate revenues from oil production and its related activities for the development of these states. The fact that equity considerations are ignored under centre-state fiscal relations is highlighted by an incident in 2001, when the federal government ordered Petronas to forgo royalty payments to the state of Terengganu. Terengganu, in response, filed a suit against Petronas because, by law, it was owed 5 percent of revenue. This occurred when Terengganu was under the rule of pas.

The foregoing discussion raises several areas of conflict. First, the areas that are designated to the states are fairly limited. The limitation arises both in terms of scope of autonomy and control and in terms of the sources of revenue. Second, political considerations take precedence over state determination of areas of priority for development. Consequently, the complaint resides in the fact that development considerations are subject to national agendas, relegating states to the status of passive recipients of federally allocated funds. Third, this passive status does not take into account disparities in horizontal differences in equity (i.e., the attempt to smooth out interstate differences in equity does not occupy a central objective in the federal government’s agenda). The pattern of budgetary allocations for state expenditures appears to be aimed neither at eradicating interstate differences nor at accounting for economic deprivation. Thus, we note that states that are less developed are not accorded a special status as far as allocations for expenditure are concerned. Even more problematic is the issue of arbitrarily denying a state its due reward for resources obtained from its territories when such returns substantially added to the federal government’s revenues.

fiscal federalism and macroeconomic management

In most areas, there is a great deal of centralization with regard to fiscal policy. It is not only fiscal policy that is concentrated in the hands of the centre but also budgetary allocations. In keeping with these observations, it is not surprising that the part of macroeconomic management that is covered by fiscal policy is also concentrated in the hands of the federal government and its respective agencies. This tendency was apparent in the aftermath of the 1997/98 financial and economic crisis, and it is a clear indicator of the powers that the centre amasses and executes in the implementation of fiscal policy.

An examination of the fiscal policy response to the financial and economic crisis clearly indicates that the federal government took complete control over the fiscal measures that were employed in response to the crisis. In almost all cases, the measures involved fell exclusively under the federal list. Clearly, the participation of the states in fiscal remedies to the crisis was severely limited.

Table 1 Basic geographic and political indicators

| Geographic | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Southeastern Asia, peninsula bordering Thailand and northern | ||

| one-third of the island of Borneo, bordering Indonesia, Brunei and | |||

| the South China Sea, south of Vietnam | |||

| Area | Total: | 329,750 sq km | |

| Land: | 328,550 sq km | ||

| Water: | 1,200 sq km | ||

| Population | 24,385,858 (July 2006 est.) | ||

| Ethnic | Malay: | 50.4% | |

| Chinese: | 23.7% | ||

| Indigenous | 11% | ||

| Indians | 7.1% | ||

| Others | 7.8% | ||

| Government | |||

| Government type | Constitutional monarchy | ||

| Note: Nominally headed by paramount ruler and a bicameral | |||

| Parliament consisting of a non-elected upper house and an elected | |||

| lower house; | |||

| all Peninsular Malaysian states have hereditary rulers except Melaka and | |||

| Pulau Pinang (Penang); those two states along with Sabah and Sarawak | |||

| in East Malaysia have governors appointed by government; | |||

| powers of state governments are limited by federal constitution; | |||

| under terms of federation, Sabah and Sarawak retain certain constitu | |||

| tional prerogatives (e.g., right to maintain their own immigration con | |||

| trols); Sabah holds 25 seats in House of Representatives; Sarawak holds | |||

| 28 seats in House of Representatives | |||

| Legislative | Bicameral Parliament, or Parlimen, consists of the Senate or | ||

| Dewan Negara (70 seats; 44 appointed by the paramount ruler, | |||

| 26 appointed by the state legislatures) and the House of Representa | |||

| tives, or Dewan Rakyat, (219 seats; members elected by popular vote | |||

| to serve five years) | |||

| Elections: House of Representatives | |||

| Election results: House of Representatives | |||

| Judiciary | Federal Court (judges appointed by the paramount ruler on the advice | ||

| of the prime minister) | |||

The degree of centralization over the use of fiscal measures is not surprising. The division of fiscal powers and responsibilities centralizes powers in the hands of the federal government. The concurrent list, which presents matters over which the centre and states have room for cooperation, is limited to matters such as social welfare, town and country planning, housing, public health, drainage, and irrigation. With those important areas over which the state has exclusive control being limited to issues that include local government, land, state government, and local public services, it is obvious that the states have a very restricted mandate over the fiscal matters that determine their well-being.

issues in revenue-raising responsibilities

The Malaysian Constitution is the definitive guide to federal-state relations, and in spirit it seeks to provide a framework where powers and responsibilities are shared between central and state governments. Although the federal and state governments are supposed to complement each other, this has not been borne out in practice. States, especially those run by the opposition parties, have frequently complained of the narrow role that is allotted for them in fiscal matters. In spite of the federalist nature of the Constitution, there has been an increasing tendency to centralize fiscal powers.

The Constitution clearly divides the sources of revenue to which federal and state governments have access. The federal government has access to direct taxes such as income tax, property and capital gains taxes, and estate duties. Other revenue sources that come under the domain of the federal government include indirect taxes such as import, export, excise, and stamp duties; sales, service, and gaming taxes; and taxes on betting, sweepstakes, lotteries, and the like. Non-tax revenue – such as road taxes, licences, and service fees – also accrues to the federal government.

The states, by comparison, have less flexibility in raising revenues as they are restricted to import and excise duties on petroleum products, export duties on timber and other forest products, and the excise duty on toddy. Other sources of revenue include income from forests, lands and mines, and entertainment duties. States also gain their revenue from non-tax sources such as licences and permits, royalties, service fees, commercial undertakings, receipts from land sales, and rents on state property. Earnings from federal grants, zakat,13 and other Islamic sources of revenue count among the sources of revenue for the states.

The Constitution provides the federal government with exclusive powers to institute and collect all taxes and non-tax revenues. Yet, on considering the division of revenue sources between centre and state, one cannot help but be struck by the asymmetry that exists between the two entities.14 The division of revenue sources between the centre and the states unarguably indicates that the sources of revenue are highly centralized, with the bulk accruing to the federal government. Given this state of affairs, the fiscal independence of states cannot be assured. Notwithstanding the fact that Malaysia is a small country, there are still valid reasons why a greater degree of fiscal decentralization should be forthcoming. First, it gives greater flexibility and autonomy for the states to determine their respective economic agenda. Second, more fiscal decentralization would also spur greater efficiency and accountability among the states, and this would encourage better governance. Third, decentralization would also reduce political patronage. Fourth, the federal government could concentrate on its role as overall coordinator rather than on its present function, which has it assessing plans and implementing projects for all the states. There are two areas in which the federal government is well poised to serve:

(1) coordinating policies and the institutional frameworks across states and (2) ensuring that interstate fiscal transfers are carried out in order to ensure interstate equity.

The available evidence does not seem to indicate that the federal government is in any way inclined to decentralize powers for the collection of tax revenues. In absolute terms, the total consolidated state government revenues for all the states in Malaysia have been rising from 1985 to the present period. Yet, on average, the rate of growth of state government revenue has been declining in recent years.15 The average annual rate of growth of state government revenue between 1995 and 2000 was about

4.9 percent. However, the average rate of growth of consolidated state government revenue from 2000 to 2005 declined to approximately 2.5 percent, indicating that the state governments’ capacity for revenue collection has diminished. This declining trend is not observed for the rate of growth of federal government revenue. The average annual growth of federal government revenue between 1995 and 2000 was about 4.4 percent, but between 2000 and 2005 it was approximately 14.4 percent. Obviously, the state and federal governments are not subject to the same set of circumstances. The trends seem to indicate that those sources of revenue open to the federal government are growing, while those open to the state governments are declining.

As far as the sources of revenue for the local governments in Peninsular Malaysia are concerned, the general provisions are enshrined under Part 3, Section 39 of the Local Government Act, 1976. Similarly, in Sabah, revenue for local government is governed by the Local Government Ordinance, 1961; and in Sarawak the same is guided by the Local Authority Ordinance, 1948. Local government revenues are composed of taxes, rates, rents, fees, fines, and property income.16 Local authorities also obtain their revenue from grants and contributions from the federal and

Table 2 Malaysia: Summary of federal and state government functions

Federal State

| 1 | External affairs | 1 | Muslim laws and customs |

| 2 | Defence | 2 | Land |

| 3 | Internal security | 3 | Agriculture and forestry |

| 4 | Civil and criminal law and the | 4 | Local government |

| administration of justice | |||

| 5 | Federal citizenship & alien naturalization | 5 | Local public services; boarding house, |

| burial grounds, pounds and cattle | |||

| trespass, markets and fairs, licensing | |||

| of theatres and cinemas | |||

| 6 | Federal government machinery | 6 | State works and water |

| 7 | Finance | 7 | State government machinery |

| 8 | Trade, commerce, and industry | 8 | State holidays |

| 9 | Shipping, navigation, and fishery | 9 | Inquiries for state purposes |

| 10 | Communication and transport | 10 | Inquiries for state purposes, creation of |

| offence and indemnities related to state | |||

| matters | |||

| 11 | Federal works and power | 11 | Turtles and riverine fishery |

| Supplementary list for Sabah and Sarawak | |||

| 12 | Surveys, inquiries and research | 12 | Native law and custom |

| 13 | Education | 13 | Incorporation of state authorities and |

| other bodies | |||

| 14 | Medicine and health | 14 | Ports and harbours other than those |

| declared federal | |||

| 15 | Labour and social security | 15 | Cadastral land surveys |

| 16 | Welfare of aborigines | 16 | In Sabah, the Sabah Railway |

| 17 | Professional licensing | ||

| 18 | Federal holidays; standard of time | ||

| 19 | Unincorporated societies | ||

| 20 | Agricultural pest control | ||

| 21 | Publications | ||

| 22 | Censorship | ||

| 23 | Theatres and cinemas | ||

| 24 | Cooperative societies | ||

| 25 | Prevention of and extinguishing fires |

Table 2 Malaysia: Summary of federal and state government functions (Continued)

Additional shared functions Shared functions for Sabah and Sarawak

| 1 | Social welfare | 17 | Personal law |

| 2 | Scholarships | 18 | Adulteration of foodstuff and other |

| goods | |||

| 3 | Protection of wild animals and birds; | 19 | Shipping under fifteen tons |

| national parks | |||

| 4 | Animal husbandry | 20 | Water power |

| 5 | Town and country planning | 21 | Agriculture and forestry research |

| 6 | Vagrancy and itinerant hawkers | 22 | Charities and charitable trusts |

| 7 | Public health | 23 | Theatres, cinemas and places of |

| amusement | |||

| 8 | Drainage and irrigation | ||

| 9 | Rehabilitation of mining land and land | ||

| which has suffered soil erosion | |||

| 10 | Fire safety measures | ||

| 11 | Culture and sports, housing |

Source: Malaysia, Constitution of Malaysia, Ninth Schedule (Article 74, 77) on “Legislative Lists.”

state governments. The Ministry of Housing and Local Government has a classification of the sources of income for all local authorities. The six categories of income that it has laid out include (1) assessment rates, licences, and rentals; (2) government grants (inclusive of road grants); (3) car parking charges; (4) planning fees; (5) compounds, fines, and interest income; and (6) loans from higher levels of government or financial institutions.

The sources of revenue, as defined by the various legal provisions, have not been modified over the years to take into account the changing realities that confront local governments. This has created vertical imbalances between the state governments and local authorities. One of the complaints from local authorities is that the assessment of property taxes, an important source of revenue, can only be increased subject to approval from the respective councils and state governments – something that involves a complicated political process. Similarly, a change in the annual value, or the value-added (selling price), of property requires a re-evaluation of the properties under question – a process that, once again, requires a lengthy exercise. Both these changes are difficult to bring about. As a consequence, the rating percentages have remained stagnant. Although the Local Government Act stipulates the ceiling rate of an assessment tax at 35 percent of the annual value of a property, or 5 percent of the value added, this is not executed in practice. Local authorities have refrained from imposing the maximum possible rating percentage. The average national percentage that is effectively implemented by the local authorities in Malaysia is about

9.8 percent, which is way below the maximum rate that can be imposed. Local authorities also face restrictions on the rates that they can effectively charge because any attempt to raise the rates will attract a great deal of censure from political quarters. In fact, local authorities find it difficult even to collect outstanding dues on assessment taxes, with many local councils in Selangor having as much as rm20 million (us$5.4 million) payable to them in arrears.

Another important source of revenue for local governments is licences and permits. These are revenues that are obtained from the licences and permits extended to small establishments such as photography shops, hawkers, provision shops, pawn shops, goldsmiths, restaurants, and launderettes. The revenue obtained through this source is a direct result of the local governments’ attempts to control and regulate the operation of these businesses. Again, these businesses are typically small, and any attempt to raise the rates that are extended to them will in all likelihood have strong political repercussions. The local governments are fully aware that an increase in licence and permit fees will only adversely affect small traders and entrepreneurs, without resulting in significant gains in marginal revenue. Nor will such an exercise serve any distribution objective; it will only lead to a loss in political popularity.

State governments in Malaysia have a limited space within which to manoeuvre the collection of fiscal revenues. The sources that have been allotted to them are fairly restricted, causing a high frequency of deficits among many state governments. Both these phenomena, in turn, result in an unfavourable degree of dependence on the federal government for funds. The only respite that is available to some states is the availability of revenues due to petroleum royalties or the taxes arising from forestry products. Most states are endowed neither with petroleum nor forest products, implying that they are mainly dependent on the federal government for support. Aside from those states that are highly industrialized and enjoy a high level of urbanization, state sources of fiscal revenue are limited.

There are problems of horizontal imbalances across the states; there are also problems of vertical imbalances within states. The sources of revenue available to local governments are limited, causing local authorities difficulty in raising funds. Those sources that can be tapped for further tax revenue (e.g., assessment taxes, licences, and permits) are those that are most sensitive as tapping them would act against distribution concerns and incur the political wrath of a significant section of the electorate.17

fiscal equity and efficiency concerns and intergovernmental fiscal transfers

In view of the high level of centralization that characterizes the Federation of Malaysia, it is worthwhile discussing how the federal government perceives questions of equity and efficiency. Of course, these issues are addressed through the intermediary of intergovernmental fiscal transfers as it is possible to level equity imbalances between states through transfers. This necessitates a review of the federal government’s position and record on fiscal transfers in order to demonstrate how it addresses these pressing questions.

The states in Malaysia traverse a range of poverty and per capita income levels as well as stages of development. The geographical area that they cover varies too. These distinctions invite differences, and fiscal transfers from the federal government to the state governments ought to bridge these differences. Indeed, an important function of the transfer mechanism ought to be an attempt to seek to support the less advantaged states. Equally, states are in different stages of development and so have different development needs, be they in the area of infrastructure, education, or health care. Daunting as the task may be, the federal government should be expected to be sensitive to the equity imbalances and development needs of the states. This is all the more important in a country like Malaysia, where, given the limited powers and sources of revenue to which the states have access, there is considerable dependence on the federal government.

Aside from reducing equity imbalances across states, intergovernmental fiscal transfers also enable local authorities to perform their obligatory duties. In Malaysia, intergovernmental fiscal transfers include launching grants, annual equalization grants, development project grants, road maintenance and drainage grants, and balancing grants. Launching grants are funds that are provided to the state governments for restructuring their local authorities, usually with the objective of providing service extensions or infrastructure development. This type of grant is calculated on the basis of land area and population.

The annual equalization grant (aeg) is used to compensate or equalize the difference between the fiscal capacity (fc) (i.e., revenue sources) and fiscal need (fn) (i.e., expenditures) of local authorities. The federal government provides the grant to the local authorities in Peninsular Malaysia in conformity with the State Grants (Maintenance of Local Authorities) Act, 1981. Sabah and Sarawak are not privy to this facility because they are governed by their own local government acts and ordinances. The aeg is calculated on the basis of the fiscal need and fiscal capacity of local authorities. Fiscal need is calculated on the basis of the total population of the local authority, population density, geographic size of the local authority area, socio-economic development rate of the local authority, and poverty rate. The Ministry of Housing and Local Government calculates fiscal capacity employing the formula: fc = 1/2 {(8.9% × Annual Value) + Administrative Revenue}.18 The fiscal residuum, fr, is the difference between fn and fc (i.e., fr = fn −fc). The federal government does not undertake to pay the full amount of the fr but, rather, gives 15 percent of the fr as the annual equalization grant. To extend the entire fr as a grant would place a heavy burden on the federal government’s finances.

The development project fund, which, again, requires the approval of the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, is extended for the implementation of socio-economic projects. The influence that the states have with regard to determining these lies in their right to propose projects that are appropriate to their needs; however, the decisions are centrally determined. Of course, these projects have to be in line with the national agenda. Local authorities are expected to use these funds for infrastructure development, social facilities, and the beautification of areas that lie within their jurisdiction. Other projects for which these funds can be used include maintenance of recreation parks, purchase of equipment and machinery, and sanitary endeavours. If there is a basic thrust to the use of the development funds, it is towards uplifting the Bumiputera community, especially with regard to the development of Bumiputera entrepreneurship and the growth of the Bumiputera industrial community. Two other categories of grants are provided for the maintenance of roads and drains.

Poverty provides one indicator of the manner in which fiscal transfers should be made, if the objective of intergovernmental transfers is aimed at promoting equity among states. Selangor is one of the states with a low incidence of poverty, which was about 2.5 percent in 1995. Wilayah Persekutuan (Federal Territory) had a lower incidence (0.7 percent) in the same year. Other states with low incidences of poverty are Penang (4.1 percent) and Johor (3.2 percent). By contrast, Kelantan (23.4 percent), Terengganu

(23.4 percent), and Sabah (26.2 percent) had high rates of poverty.

Using a different criterion, Kelantan, Kedah, Sabah, and Perlis are the four states with the lowest per capita gdp. Kelantan and Kedah are consistently at the bottom of the ranking list with regard to both criteria, but Sabah and Perlis are not. Terengganu was one of the states with a relatively high per capita gdp in 1995, although the incidence of poverty in this state was less comforting. Those states that performed well in terms of per capita gdp included the Federal Territory, Terengganu, Selangor, and Penang.

The evidence on federal government grants suggests that Sarawak, Sabah, Johor, and Kedah have been receiving the highest grants, with Sabah and Sarawak receiving grants far in excess of the other states. This ranking of preference suggests that all is not in order as the incidence of poverty does not appear to be a dominant factor in deciding the distribution of grants.

Table 3 Federal government development expenditure: A functional classification1

Economic services

| Period | Total (rm million) | Defence and security | Subtotal | Agriculture and rural development | Trade and industry | Transport | Public utilities | Others | Subtotal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 14,051 | 2,888 | 6,440 | 1,360 | 1,218 | 3,151 | 654 | 57 | 3,513 |

| 1996 | 14,628 | 2,438 | 7,693 | 1,182 | 1,212 | 4,530 | 733 | 36 | 3,984 |

| 1997 | 15,750 | 2,314 | 7,501 | 1,105 | 1,285 | 3,578 | 1,496 | 37 | 4,919 |

| 1998 | 18,103 | 1,380 | 9,243 | 960 | 3,227 | 3,062 | 1,968 | 26 | 5,783 |

| 1999 | 22,614 | 3,122 | 8,969 | 1,088 | 2,798 | 2,893 | 1,850 | 340 | 6,936 |

| 2000 | 27,941 | 2,332 | 11,639 | 1,183 | 3,667 | 4,863 | 1,517 | 408 | 11,076 |

| 2001 | 35,235 | 3,287 | 12,725 | 1,394 | 4,830 | 5,042 | 1,092 | 367 | 15,384 |

| 2002 | 35,977 | 4,333 | 12,433 | 1,364 | 3,474 | 5,401 | 1,808 | 387 | 18,043 |

| 2003 | 39,353 | 6,029 | 13,793 | 1,620 | 3,456 | 7,354 | 920 | 443 | 17,707 |

| 2004 | 28,864 | 4,133 | 11,851 | 2,881 | 1,201 | 6,630 | 945 | 193 | 10,260 |

| 2005 | 30,534 | 4,803 | 14,957 | 2,482 | 3,221 | 7,660 | 1,481 | 112 | 7,450 |

Source: Monthly Statistical Bulletin, December 2006

1. Data at state level disaggregation is generally not available. Thus, comparable data on expenditure by function at state level is not included.

However, on the basis of per capita gdp, Sabah and Kedah do deserve the treatment that they have been accorded. At any rate, it is difficult to justify why Johor and Sarawak should top the list for federal government grants. Sarawak, it should be remembered, is a recipient of petroleum royalties and taxes derived from forestry products, and Johor is a state that ranks well in terms of various development indices.

There are complaints that the federal government does not undertake its responsibility of resolving horizontal imbalances in a transparent or equitable manner. Development allocations, made over the five-year plan periods, reflect some biases. Penang’s development allocation is extremely high and completely out of proportion in light of its small geographical area. In terms of area (allocation per 1,000 square kilometres), Sabah, Sarawak, and Pahang fared poorly. To some extent, the attention that Pahang deserves has been redressed in the Ninth Malaysia Plan (9mp), with this state receiving 15 percent of the total federal government’s development allocation; but Sarawak is neglected under this plan, having been allocated only 1.2 percent of the total allocation.

| Malaysia | 197 | |

|---|---|---|

| Table 4 Malaysia: Summary of federal and state government revenue | ||

| Federal | State | |

| Tax revenue | Tax revenue |

1 Direct taxes 1 Import and excise duties on petroleum

i Income tax product and export duties on timber and Individuals other forest products for Sabah and Companies Sarawak, excise duty on toddy for all states Cooperatives Petroleum tax 2 Forests Development tax 3 Lands and mines

ii Taxes on property and capital gains 4 Entertainment duties Real property gains tax Estate duty

2 Indirect taxes Non-tax revenue

i Taxes on international trade and non-revenue receipts Export duties: 1. Licences and permits palm oil, petroleum 2. Royalties Import duties: 3. Service fees tobacco, cigars, and cigarettes, 4. Commerical undertakings, water, gas petroleum, motor vehicles, surtax ports, and harbours on imports 5. Receipts from land sales

ii Taxes on production and 6. Rents on state property

consumption 7. Zakat, fitrah, and Bait-ul-Mal, and Excise duties: heavy fuel oils, similar Islamic religious revenues Petroleum, spirits, motor vehicles 8. Proceeds, dividend, and interests Sales tax 9. Federal grants and reimbursements Service tax

iii Others Stamp duties Gaming tax Betting and sweepstakes Lotteries Casino Pool betting duty

Non-tax revenue and non-revenue receipts 1 Road tax 2 Licences 3 Service fees 4 Fines and forfeitures 5 Interests 6 Contribution from foreign government

and international agencies 7 Refund of expenditure 8 Receipts from other government agencies 9 Royalties

Little that is innovative is being done to correct vertical imbalances. The state and local governments have very limited powers available to them. This continues to be a nagging problem as the costs of development projects, maintenance and repair, and provision of public services have kept rising, yet the state and local governments do not have the tax room to raise revenues. Many of the sources of revenue that are available to the state and local governments are unable to yield higher revenues in that any attempt to raise them will trigger political dissatisfaction. To make matters worse, there has been a tendency to shift away from the provision of grants towards the extension of loans to state governments. This is likely to result in the more developed states having the resources to develop further and to provide better public services than the less developed states.

financing capital investment

The federal government has, according to the powers vested in it by the Constitution, the right to determine those items that it deems necessary for capital investment. Capital investment for these items is budgeted in the five-year plan documents under the category of development expenditure. Typically, the five-year plans allocate expenditure on specified items to the various states. However, the annual national budget determines the actual payment that is made to the states. In other words, although central government spending is allocated within the format of a five-year plan, transfers are carried out on an annual basis. Financing for these projects, as far as domestic sources of financing are concerned, comes from direct and indirect taxes as well as from non-tax revenue. Tax and non-tax revenues are not the only sources of finance. The federal government finances its capital expenditure through domestic borrowing; it also takes loans from bilateral lenders and multilateral institutions. Direct taxes are the major contributor to federal government revenue. However, in recent years the rate of growth of direct taxes has been decreasing because the government has been making attempts to provide a more competitive tax structure, with the intention of attracting investors to Malaysia. The rate of growth of indirect taxes has been exceeding that of direct taxes. Non-tax revenue, on average, contributed about 20 percent of total federal government revenue over the Eighth Malaysia Plan (8mp) period (2001–05).

Non-financial public enterprises (nfpfes) are the public entities in Malaysia that incur the largest capital expenditures. nfpes include Petronas (National Petroleum Company), Sarawak Electricity Supply Corporation (sesco), and Tenaga Nasional Berhad (National Energy Company). The federal government makes development allocations for the capacity expansion of these companies, as it did during the 8mp period, accommodating the expansion of the national grid and upgrading transmission lines so as to meet the growing demand for electricity. This, as well as several large-scale petrochemical projects that Petronas had launched, were major objects of capital expenditure. A source of contention is the fact that the financial statements of these nfpes are not always open to public scrutiny, Petronas being a prime example. Consequently, there is no transparency in the financial standing of such entities – an unfortunate instance of poor governance, especially when public funds are at stake.

The Local Government Act, 1976, empowers local governments with the legal standing to borrow. This borrowing can be done through mortgages, overdraft facilities from private banks, and issues of stock and debentures. Local governments can also borrow from state and federal governments. Although in theory the local authorities could borrow from a wide range of sources, in practice they have been limited to the federal government. This is because the local authorities require the approval of the respective state governments, and these have been rather conservative in their choice of sources of finance.

To summarize, the federal government has complete control over the items requiring capital investment that affect the nation as a whole, including such items as expenditure on defence, education (public universities and schools), and infrastructure (ports, airports, bridges, and dams). The financing of these items of capital investment goes through the normal budgetary process. Since the 1980s, the federal government has increasingly resorted to privatization as a way of reducing its fiscal burden. Privatization in this context has not been untainted as there have been accusations of crony capitalism at work; and, at any rate, economic considerations such as efficiency have not been the guiding principle in the privatization process. Further, the process of public procurement has not been as transparent as it should be, throwing the principles of accountability, transparency, and efficiency to the wind.

The narrowness of the list of areas in which the states can exercise power through capital investment diminishes the power of the states. The states are stripped of their autonomy over issues that would best be left in their hands. This, by implication, ignores local preferences. Because state matters that would imply significant capital investment are really decided by the centre, the federal government’s powers are reinforced and concentrated. We need to be reminded that issues such as transportation, education, and health, for instance, are on the federal list. For those matters that require state funding, the states, where possible, finance their own capital expenditure; otherwise, the states seek the indulgence of the federal government. Local authorities must obtain the endorsement of local agencies (such as the Department of Public Works), which, with the support of the state government, is forwarded to the Ministry of Finance for approval.

fiscal federalism dimensions of the public management framework

There are civil servants who attend to the duties that are associated with the offices of the federal, state, and local governments. Civil servants who work in the federal and state governments are quite distinct with regard to the recruitment processes that they have to go through. Those who wish to serve in the federal government have to be selected for training by the Malaysian Administrative and Diplomatic Service. An officer who is selected for appointment by a particular level of authority remains there for the duration of his career.

Individual states are responsible for staffing their local authorities, which have the power to recruit their own staff. The power to discipline and dismiss staff also lies within their ambit. Occasionally, senior civil service staff from the centre are seconded to local governments as council presidents. The recruitment process for employment in local government is by no means unorganized; rather, it is based on the principle of merit and seeks to appoint on the basis of intellectual ability, professional or technical expertise, and integrity. Subsequent to selection by the relevant board, the appointment is not made until appropriate clearance is obtained from the state government, the treasury, and the Public Service Department. A frequent complaint that is voiced against the selection of civil servants both in the local and federal governments involves the racial bias that seems to be attached to the selection process as the vast majority of officers are Bumiputera. The government has responded to this complaint by stating that the non-Bumiputera have not shown an interest in civil service positions.

It cannot be denied that, in so far as the administrative machinery is concerned, there is some interference from the federal government in running local government. The public management apparatus at the district level is headed by the district officer, who is usually a federal government appointee – a civil servant who is a member of the Administrative and Diplomatic Service. The only states that make appointments for the district position from their own state civil service are Sabah, Sarawak, and Kelantan. The appointment of district officers by the federal government is a critical move because all projects targeted at the district level have to be discussed at various committees, and these are often chaired by the district officer. This ensures that the federal government’s interests prevail.

There have been veiled comments that there is some degree of corruption among government officers. The government’s response to these remarks has been to expose those officers guilty of corruption to the Anti-Corruption Agency. The present prime minister, Abdullah Badawi, has launched a campaign against corruption and, in so doing, has reiterated a stand that the previous prime minister, Mohammed Mahathir, undertook early in his career: to pursue a “clean, efficient, and honourable” administration. The collapse of national trunk roads and cracks in school buildings have also led to some speculation about the system of awarding government contracts and the subsequent monitoring of projects.

The civil service is not the premier choice of employment that it was prior to the 1980s. Government officers and civil servants themselves complain of salary scales that do not reflect present market conditions. There is also much dissatisfaction with the fact that promotions are slow and not always based on merit and performance.

the way ahead

Although Malaysia is a federation, much needs to be done to achieve a greater modicum of decentralization. As it stands, the division of powers and responsibilities is heavily in the hands of the centre; and while that is not without some advantages, the arguments in favour of more decentralization are urgent and compelling. One of the more pressing issues that centralization has not addressed very successfully is the question of equalization, because, on the one hand, a small number of states have achieved a respectable level of development; on the other hand, there are a number of less developed states. The federal government does not seem to have had much success in identifying and addressing these imbalances because, repeatedly, it allocates funds to states in a manner that is not sensitive to geographical size, incidence of poverty, or level of development. It is possible that a more decentralized fiscal system would handle issues of this sort without being distracted by factors such as ethnic origin and political loyalty.

Some issues, such as education, health care, and transportation, are intrinsically more suited for consideration by the states than are others. If there were concerns that decentralizing decision making on these issues would result in policies that are at odds with national policies, then an approach that involves the federal government playing the role of coordinator could be taken. At any rate, to persist with a centralized approach would mean long time lags, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and a loss in effectiveness in serving the local populace.

More urgently, it is necessary for the federal government to explore ways in which the sources of revenue open to the state governments are enlarged. This can be done in two ways: (1) through the devolution of powers to the state and (2) through the introduction of non-conventional sources of taxation. With regard to the latter, it is possible for the state governments to lease state land, trade in emissions, or levy road congestion charges. The devolution of fiscal powers to the states is a more straightforward affair and must be seriously considered.

Efforts must also be made to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of civil servants and personnel employed in government offices. This requires a system that can demand greater accountability and efficiency from officers employed in the federal and state governments. There have been attempts to upgrade the salaries of certain sections of government personnel. This has been done by increasing the bonuses due to them and by providing for increments in salaries that are commensurate with performance. Despite these arrangements, their productivity has not increased, and this suggests that a system that is based on productivity needs to be introduced.19

acknowledgment

I would like to thank Anwar Shah, John Kincaid, Suresh Narayanan, and two anonymous referees for comments on earlier versions of this chapter. The usual disclaimer holds.

notes

1 For useful discussions on the nep, see K.S. Jomo, “Malaysia’s New Economic Policy and National Unity,” Third World Quarterly 11, 4 (1989): 36–53; and R. Klitgaard and R. Katz, “Overcoming Ethnic Inequalities: Lessons from Malaysia,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 2, 3 (1983): 333–49.

2 For a discussion of Malaysia’s economic transformation, see K.S. Jomo, Growth and Structural Change in the Malaysian Economy (London: Macmillan, 1990). 3 See M. Ariff and H. Hill, Export-Oriented Industrialisation – The asean Experience

(Sydney: Allen and Unwin, 1985). 4 For background on the history and political processes of federalism in Malaysia, see

B.H. Shafruddin, “Malaysian Centre-State Relations by Design and Process,” in Between Centre and State: Federalism in Perspective, ed. B.H. Shafruddin and I.A.M.Z. Fadzli, 2–28 (Kuala Lumpur: Institute of Strategic and International Studies of Malaysia, 1988); and B.H. Shafruddin, The Federal Factor in the Government of Peninsular Malaysia (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987).

5 For a thorough discussion of the structure of government in Malaysia, see

R.S. Milne, Government and Politics in Malaysia (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1967). 6 See Government of Malaysia, Federal Constitution (Kuala Lumpur: Government

Printers, 1988). 7 For an understanding of how local governments function in Malaysia, see

S.N. Phang, Sistem Kerajaan Tempatan di Malaysia (Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1997).

8 See K.S. Jomo and C.H. Wee, “The Political Economy of Malaysian Federalism: Economic Development, Public Policy and Conflict Containment,” Journal of International Development 15: 441–56.

9 See K.S. Jomo and C.H. Wee, “The Political Economy of Petrol Revenue under Malaysian Federalism,” paper presented at the Workshop on Human Rights and Oil in South East Asia and Africa, organized by the Berkeley Centers for African Studies and Southeast Asia Studies, University of California, Berkeley, 2003.

10 See S. Nambiar, “Malaysia’s Response to the Financial Crisis: Reconsidering the Viability of Unorthodox Policy,” Asia-Pacific Development Journal 10, 1 (2003): 1–23.

11 See S. Narayanan, “Towards Economic Recovery: The Fiscal Policy Side,” paper presented at the mier 1999 National Outlook Conference, Kuala Lumpur, December 1998, and V. Vijayaledchumy, “Fiscal Policy in Malaysia,” Bank of International Settlements Papers 20, 2003.

12 See M.H. Piei and T. Tan, “An Insight into Macroeconomic Policy Management and Development in Malaysia,” in Rising to the Challenge in Asia: A Study of Financial Markets, Asian Development Bank (Manila: Asian Development Bank, 1999).

13 Zakat refers to a compulsory levy on each Muslim who has wealth equal to or greater than a minimum, referred to as Nisab (which is approximately us$1,400 per year).

14 See S. Wilson and S. Mahbob, “Decentralisation and Fiscal Federalism in Malaysia,” in Malaysia’s Public Sector in the Twenty-First Century, ed. S. Mahbob, F. Flatters,

R. Boadway, S. Wilson and E.S.L. Yin, 146–64 (Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Institute of Economic Research, 1997). 15 See K.S. Jomo and C.H. Wee, “The Political Economy of Malaysian Federalism,”

Discussion Paper No. 2002/113, United Nations University/Wider, 2002. 16 For a comprehensive overview of revenue raising and the local government, see

S.N. Phang, Financing Local Government (Kuala Lumpur: Universiti Malaya, 1997).

17 For some recommendations on sources of revenue for local government, see Setapa Azmi, “Study on the Development of Government Bond Markets in Selected Developing Member Countries: The Case of Malaysia,” paper presented at the Asian Development Bank Conference on Local Government Finance and Bond Market Financing, Asian Development Bank, Manila, 19–21 November, 2002.

18 See Ministry of Housing and Local Government, Laporan Program/Projek Pembangunan Jabatan Kerajaan Tempatan dan Kedudukan Kewangan, September 1995.

19 No data on vertical fiscal gaps is available for Malaysia. For this reason, I was unable to include the appropriate table.